Hello Dear Reader,

The idea for this blogpost came to me a few days ago as I was rereading a fairy tale “The Fir Tree” from one of my old childhood books, “Andersen’s Fairy Tales” (Bulgarian translation). Above is a picture of my tattered old book, it is missing some pages and that is not surprising at all because the glue is mostly gone, and the pages no longer hold together.

In fact, this is not the actual copy I had as a child, but it is the exact edition which I found thanks to the Internet and ordered all the way to Canada. This book was published in 1977 and was illustrated by Lyuben Zidarov who, apparently, was the oldest working illustrator in Bulgaria, and who died this year at the venerable age of 100.

In all honesty these were not my favorite illustrations, I have other books in my childhood collection of fairy tales with illustrations which I enjoyed much more as a child. Looking now at Zidarov’s illustrations I can appreciate their beauty and his childlike vision and technique, but as a child I did not want to look at pictures that reminded me of my own drawings which I always found rather disappointing because they never looked like what I had in mind.

Reading Andersen’s fairy tales as a child is something that I share with P.L. Travers. She writes in “The Black Sheep”, an essay first published in The New York Times in 1965 and then republished in her last book “What the Bee Knows”, about enjoying his stories as a child, “I even wallowed in it, yet I never could quite understand why I felt no better for it.” she writes.

As an adult and writer, herself, P.L. Travers did not appreciate the tortures Anderson inflicted on his fictional characters; these torments she perceived to be disguised as piety and to have a demoralizing effect on the reader. The other reproach she made to Andersen was that he never invented a strong villain, that all he wrote about were white sheep, “…some clean, some dirty, but a homogenous flock”. She preferred, she wrote, the strong contrast of the Grimm’s fairy tales.

I tend to agree with P.L Travers on many things and she has been a great posthumous teacher for me. Yet, when it comes to Andersen, we seem to hold different views. Andersen’s fairy tales are undoubtedly heart-wrenching, but there is so much meaning in them, and he possessed such an incredible talent as a storyteller that I find it difficult to conceive that she was oblivious to it all. Sometimes I wonder if she genuinely meant her harsh critique, or if she enjoyed expressing strong opinions to shock the reader and prompt reflection.

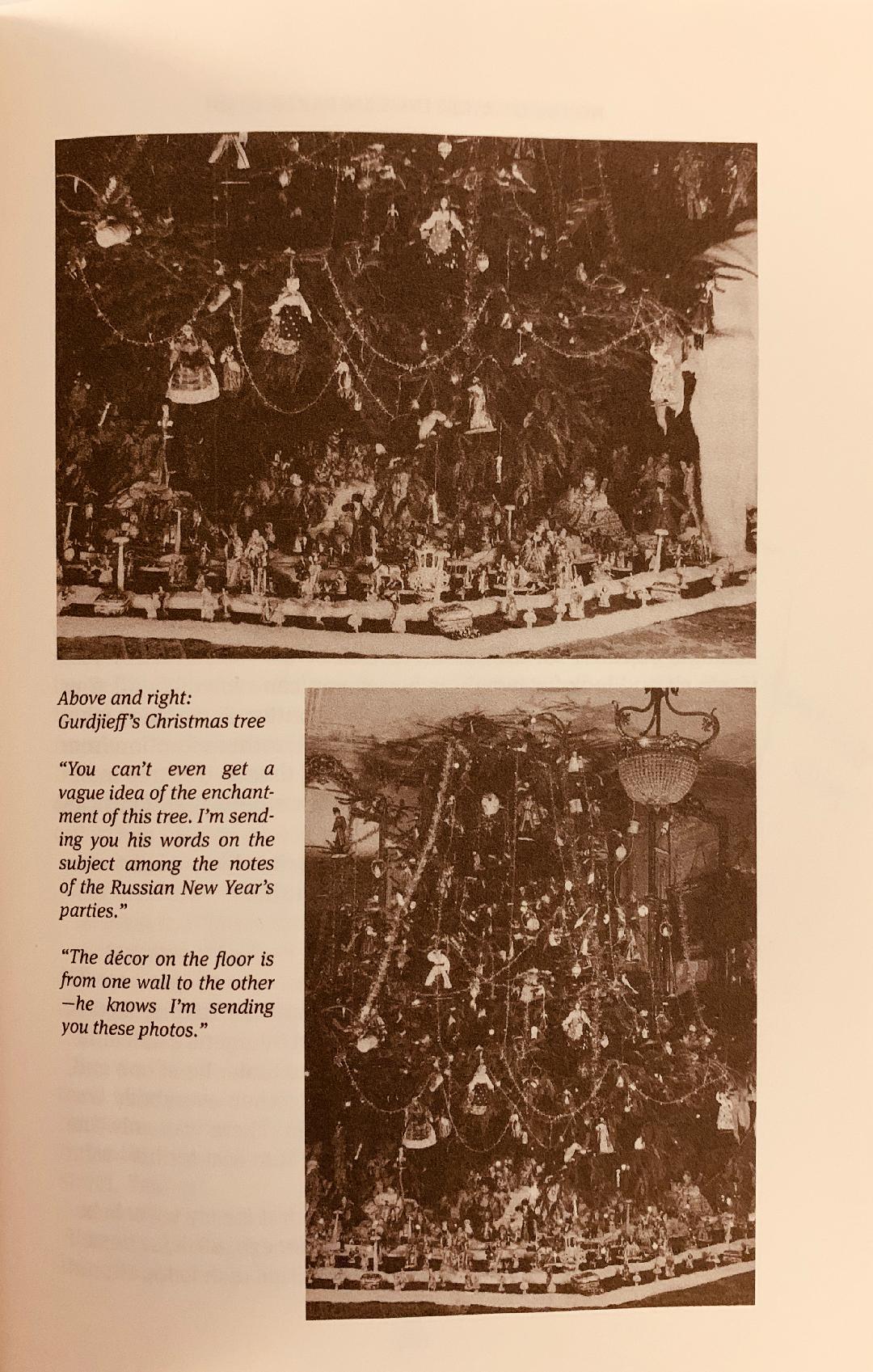

And I see a connection here that I would have loved to discuss with P.L. Travers. Andersen seems to teach through pain; his use of emotional torture aims to awaken the reader to a deeper truth. I wish I could ask P.L. Travers how his technique differs from the one used by her beloved spiritual teacher Gurdjieff who said that one can only awaken through conscious suffering?

When I first read “The Fir Tree” as a child, I thought it was a sad and strange New Year’s Eve story about a New Year’s tree abandoned in the attic after the celebrations and later burned outside in the yard. (I say New Year because in the 1980’s we did not celebrate Christmas in Bulgaria; religion was forbidden by the communist regime. Instead, we celebrated the New Year and decorated a fir tree, and Santa Clause was not Santa Clause but Father Frost.) Anyhow, I simply turned the page and conveniently forgot about the story of the fir tree, as I couldn’t fathom a New Year’s Eve without a New Year’s tree in the house. It was that easy.

But it was not that easy the second time around. As I reread the story I almost agreed with P.L. Travers on the subject of Andersen. It made me so very sad, and I wanted to be joyful – it is Christmas after all, the most joyful time of the year. Why take a Christmas tree and use it as a metaphor for our fleeting lives and our inability to appreciate the moment?

For some reason, I couldn’t just forget about it as I closed the pages of the book. I felt really upset, but then, I should have known better than to read a story by Andersen during the Holidays, especially one that I knew had a sad ending. I knew it was not fair for me to be upset with Andersen; it was not like he had forced the book into my hands. There was only one thing I could do to free myself from the strong emotions, and that was to write this post.

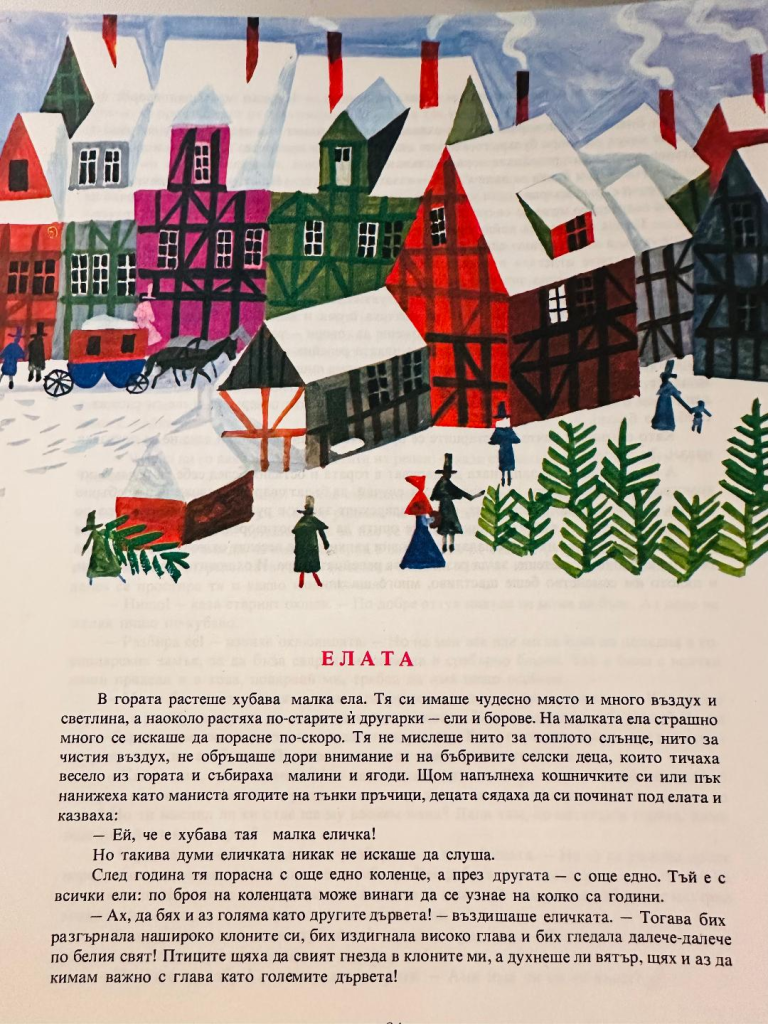

I will summarize the story briefly here for those of you who are not familiar with it. It is about a small fir tree so eager to grow up and be like the other tall fir trees in the forest that it does not notice the fresh air and the sunshine, nor the birds and the rabbits playing around it, or the pink clouds in the sky. However, it does notice that sometimes the tall fir trees get cut down and taken away to some mysterious place, and it wants to know where.

One day, the sparrows tell the little fir tree that they had seen the greatest splendor imaginable through the windows in town. They had seen fir trees beautifully decorated with gilded apples, gingerbread, toys and candles standing in the middle of warm rooms. The fir tree begins to long for a warm room in town.

The day comes when the fir-tree is finally cut down and taken to a house. Nets cut out of colored paper and filled with sweets are hung on its branches. Gilded apples and walnuts are fastened to the tree, and many colorful candles are fixed to its branches. The tree begins to anticipate what happens next and longs for the candles to be lit. All the questioning and longing cause the bark of the tree to ache, much like a headache would have done had the tree been human instead.

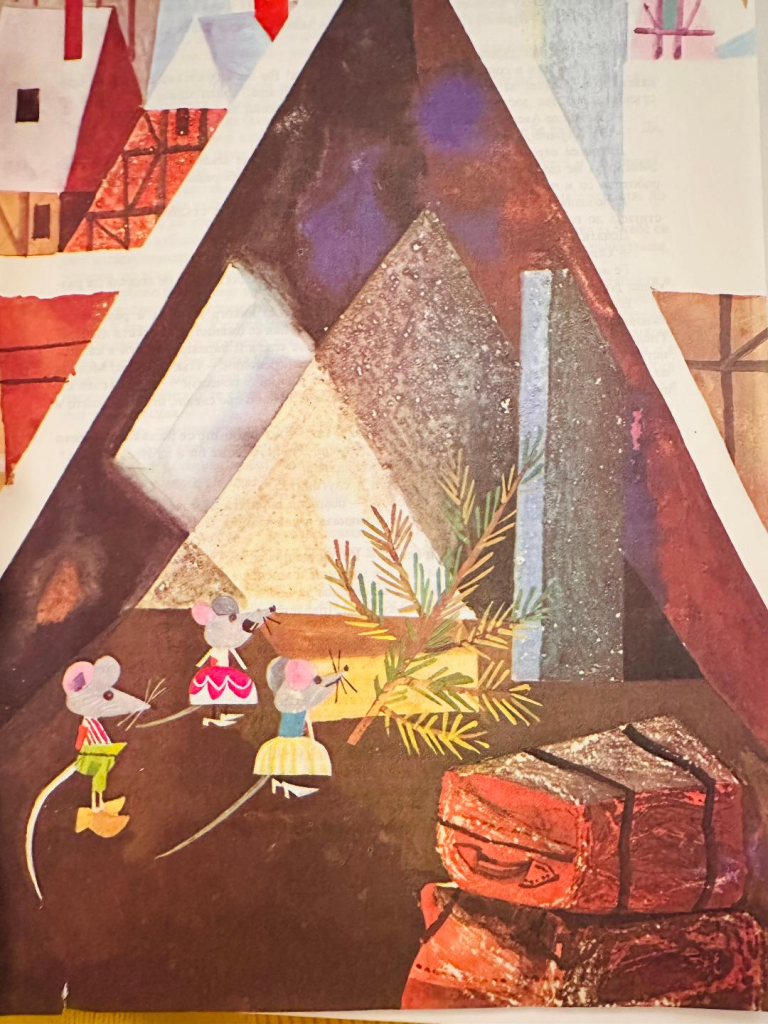

Then the candles are lit, the children come and take down the sweets and the toys hung on the branches, and the whole thing is over before the tree can even realize it. The next day, the tree is thrown in the attic where it stays for many days. The tree is sad and lonely, but one day, mice come to see it, and it begins to tell them the story of its life – where it came from and how it got to the house. All the while, it realizes that what it had was wonderful; only it did not know it back then. Not long after, the tree is taken outside and is chopped and burned in the fire under a large copper. The End.

There is such a profound truth in this story, yet those who can truly feel the sadness of it are probably those who had gone through enough of life to awaken to the realization that all stories come to an end, and there is nothing else but the present moment. I wonder if those who need the lesson can get it from a story, or is it that we always need to learn from experience? This too is a question that I would have loved to ask P.L. Travers?

I cannot say I was much wiser than the fir tree when I was younger, and it is perhaps my own grief over time wasted in futile projections that made me react so strongly when I read the story. A consolation, at least, is that we do not have a real Christmas tree in our home. I decided many years ago that it was a waste to cut down a living tree just to decorate it for a few days and then discard it without a second thought. I decided to not participate in this trade, and I wonder now, was my decision somehow influenced unconsciously by this story that I had read as a child? I think now that it is possible.

May you all fully enjoy the present moment this Christmas without projecting into the future or into the past. Although, in some cases, as in the case of Scrooge, that may be advisable… After all, what do I know?

Merry Christmas!