Dear Reader,

As a devoted fan of P.L. Travers, you can only imagine my delight in having the opportunity to learn firsthand about a private conversation she had with bestselling fantasy author Gregory Maguire back in 1995, a year before her passing. I hope that reading this blog post will be as much of a treat for you as it was for me to write it.

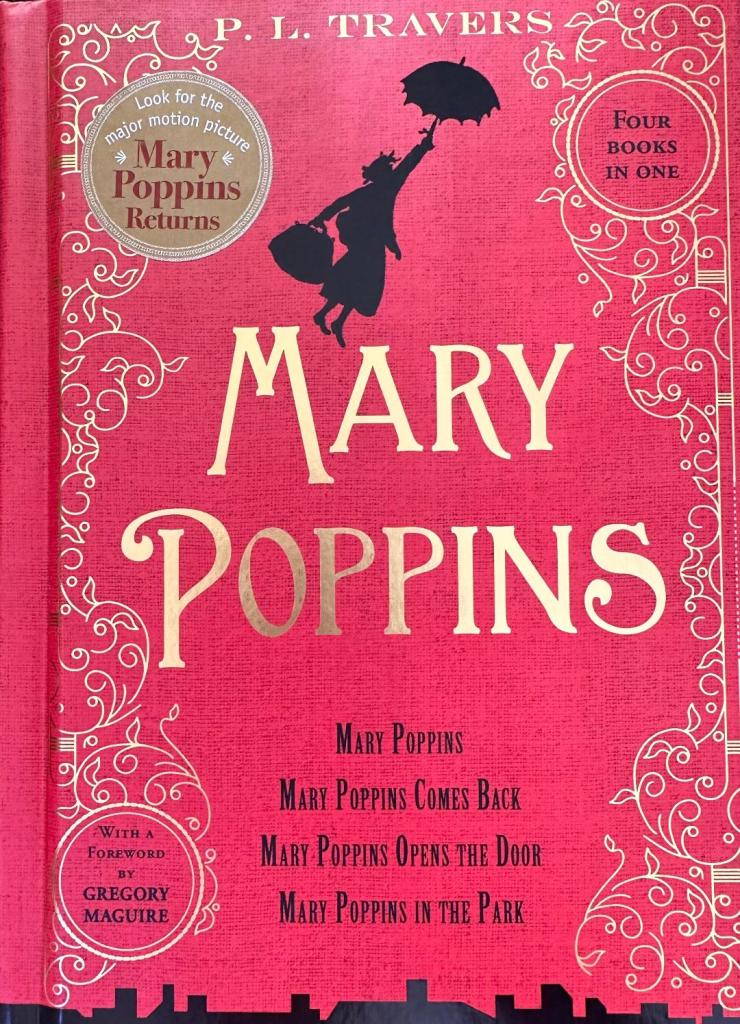

As a young boy, Gregory Maguire loved the Disney adaptation of Mary Poppins, but he loved the books more. And I believe that this is the case for most of us who first encountered the magical nanny on the page. It was certainly my own experience, but then I never saw Disney’s Mary Poppins as a child growing up behind the Iron Curtain. My acquaintance with the cinematographic version of Mary Poppins came much later and at a time when my mind had acquired its critical abilities.

“The movie is sunny and as sweet as a spoonful of sugar. The books, though, show glimmers of a far more mysterious and even dangerous world. For thirty years before the nanny began to sing on the screen, she stalked the pages of these books with ferocity and power.” (Foreword by Gregory Maguire, Mary Poppins Collection published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2014)

I couldn’t agree more!

At the time of his meeting with P.L. Travers, Gregory Maguire was at a turning point in his writing career as he was just about to publish his bestselling novel “Wicked”. He was living in London, and after discovering that the author of Mary Poppins also lived there, he sent her a note, and in return received an invitation for tea.

He showed up at Number 29, Shawfield Street, London on the appointed day and time with three of P.L. Travers’s books: one of the Mary Poppins books, “The Fox at the Manger” and “Aunt Sass”.

He found P.L. Travers “an old woman slumped in an upholstered chair set back from the window” in a “shadowy parlor that hadn’t been fluffed up recently”.

The meeting lasted for about an hour, but it was long enough for P.L. Travers to plant a seed for a story in her visitor’s fertile imagination. It was a comment she made about a fairy tale character, the youngest brother in the fairy tale “The Six Swans” by the Brothers Grimm. In this story the wicked stepmother turns her stepchildren into swans, and it is their sister who, in the end, breaks the spell by knitting shirts from aster flowers. Only she does not have enough time to finish the last shirt and the youngest brother is left with one swan wing instead of an arm.

P.L. Travers felt, and rightfully so, that there, at the end of one story, was the beginning of another.

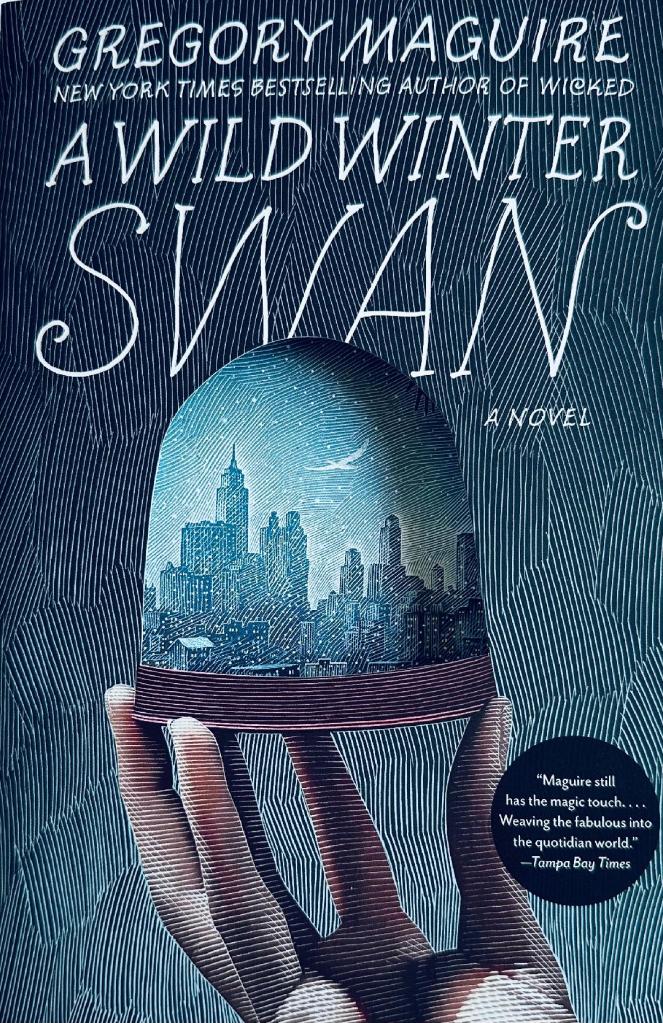

Shortly after Gregory Maguire finished writing his book “A Wild Winter Swan” but before its publication in 2020, he came across in his hand-written journals from 1995 something about P.L. Travers having said to him, “There’ a story – the sixth brother. Give him something to do. The boy with a wing. You know the one I mean?”

As the swan boy had been a beloved figure in his psyche ever since reading Hans Christian Andersen’s beautiful retelling of the Grimms’ fairy tale at the age of ten or twelve, her remark had evidently stuck in his subconscious. But that’s where Gregory Maguire tells us, seeds to stories wait.

This is by far the most exciting interview I have had the opportunity to conduct so far, but before we dive into it, and with Mr. Maguire’s permission, I am reproducing a portion of his lecture “The World at Hand, The World Next Door” presented by the Osborne Collection of Early Children’s Books for the 32nd Annual Helen E. Stubbs Memorial Lecture in November of 2019. Here is his charming recollection of his meeting with P.L. Travers.

I was living in London. Because somehow, I came across her home mailing address—perhaps in the phone book—I’d written to the author of MARY POPPINS, Ms. P. L. Travers, to thank her for her great work. She’d replied in a shaky hand ordering me to come to tea Tuesday week. Perhaps she preferred to receive tribute in person, I thought. (…) It’s nearly time to go—Number 29 Shawfield Street, London. . . .

A Georgian [row] house with a broad single window, behind palings, a small house on the east side of the street, behind a shocking pink door . . . at street level. The doorbell sharp and hard. I thought she might have forgotten, might not be there. A young woman, maybe part Jamaican, came in jeans and answered the door.

P. L. Travers sat in a chair in the corner, angled so she could watch out the window. She looked up when we came in and said to me, “Who are you?” I introduced myself—and she seemed not to hear me, but when I said again, more slowly, “Gregory” she appended “Maguire.” “You invited me to come by, and so I have, for a very short time,” I said. Mostly, in her face, were eyes and smile; she smiled like a small child; she seemed happy at everything, and smiled as a way of conversing. I had heard she was a bitch, a tart and difficult woman, but only at the end of my visit did one small comment erupt.

What follows is a sort of dialogue I devised that day out of notes I scribbled down on the back of a checkbook immediately after I had left Ms. Travers’ home. By this I mean it is more scripted than it may have sounded as it occurred—one can’t help imposing logic on scribbled notes. But the exchanges are verbatim as I could recall them even if they didn’t come out as sequentially as I put them down. Only a few words have been changed, for clarity.

PLT: I’ve been in the hospital and the nursing home for two years. I just got back. I can move very little.

GM: Can you get out at all?

PLT: Up and down the street.

GM: To the end.

PLT: To the second lamp-post. My world has shrunk to the second lamppost. But when I was out the other day, looking down to watch my feet, I found a present—

GM: —?

PLT: A star. A star!—there in the pavement. I’d never seen it there before. There’s a story—the sixth brother. Give him something to do. The boy with a wing. You know the one I mean

GM: Yes (I thought I might but wasn’t certain).

PLT: At the end of the street is a pub called the World’s End.

GM: At the other end, on the King’s Road, is a café called the Picasso Café. I sat there and a storm came up, and a rainbow came over—just ten minutes ago.

PLT: That was for you, to show you that you’re welcome here.

GM: You live between the star and the rainbow.

PLT: Yes! . . . . this is my whole world. There used to be… acres and acres of lavender, and cows mooing.

GM: Where is Cherry Tree Lane?

PLT: What?

GM: Where in London is Cherry Tree Lane supposed to be?

PLT: I don’t know what you mean.

GM: The house that Mary Poppins lived in. Is it in Chelsea? In Kensington?..

PLT: Oh! Well, no. Well, it’s…. it’s…. (she waves her hand)… It’s between here and someplace else.

GM: Do you know, I grew up on Mary Poppins. When I was ten years old, I sat on our front porch and read the books and ate sour-apple hard candy. I never forget it.

PLT: Do you know, when I came home from hospital, I picked up the second Mary Poppins book, and I began to read it. And I didn’t know what was going to happen! I turned the pages—I found it delightful. …. I didn’t know what would come next.

GM: I’m not surprised. She’s a mystery.

PLT: I don’t think we’ve seen the last of her. . . .

GM: Will you sign a few books?

PLT: It is hard to do.

GM: Maybe three? This is MARY POPPINS AND THE HOUSE NEXT DOOR.

PLT: And this is something special for you. (She draws a star). William Butler Yeats told me only to sign my name, but this is for you.

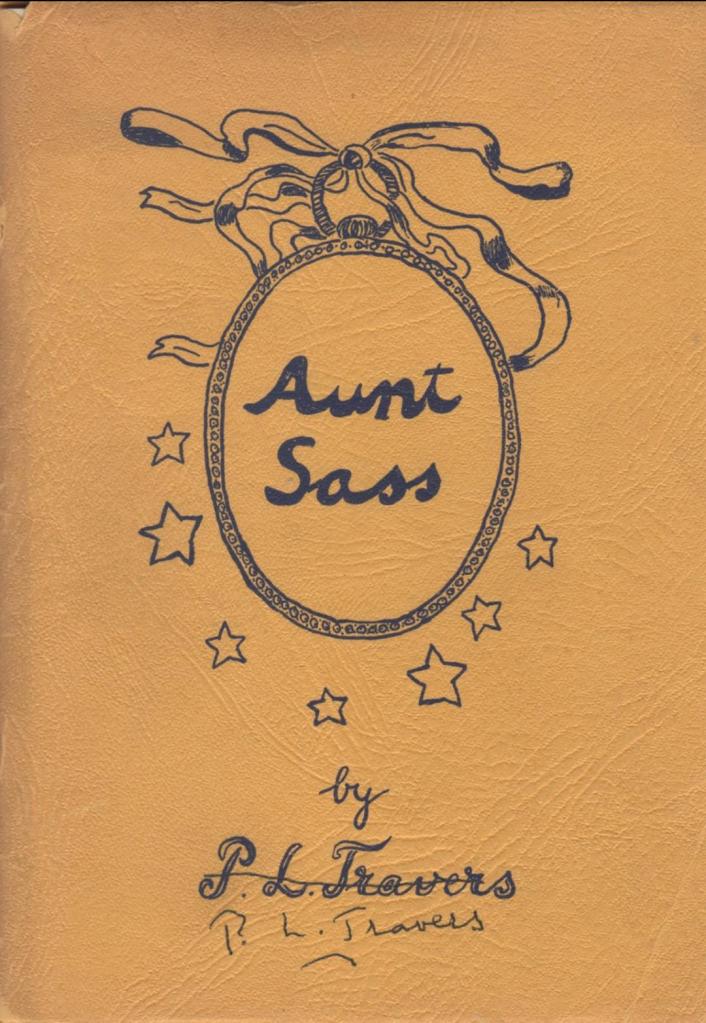

GM: Do you remember this? (A privately printed copy of AUNT SASS, which Travers had once had done up as a Christmas present for close friends.)

PLT: ! (She opens it.) Look! Stars! Nine stars! Who put those there? But where’s my name?

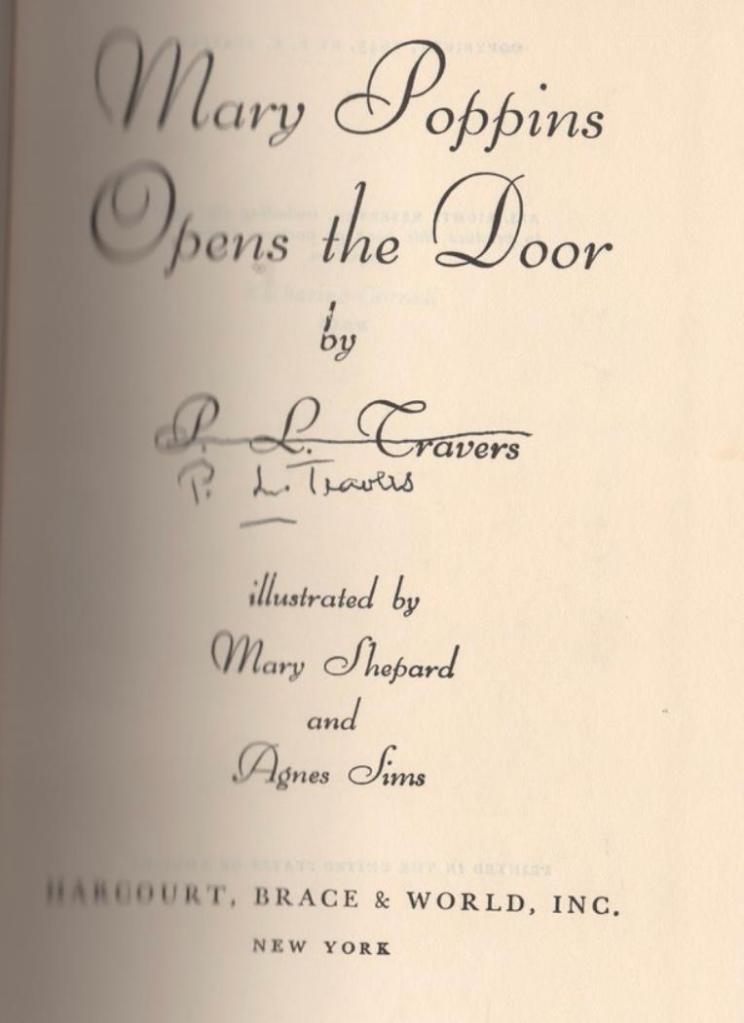

GM: On the front. (She crosses out the printed name and signs her own name.) And this last. MARY POPPINS OPENS THE DOOR. It’s my favorite.

PLT: It’s not for children.

GM: It’s Mystery. Mystery is for children.

PLT: Yes, but also for adults.

GM: Yes. Of course.

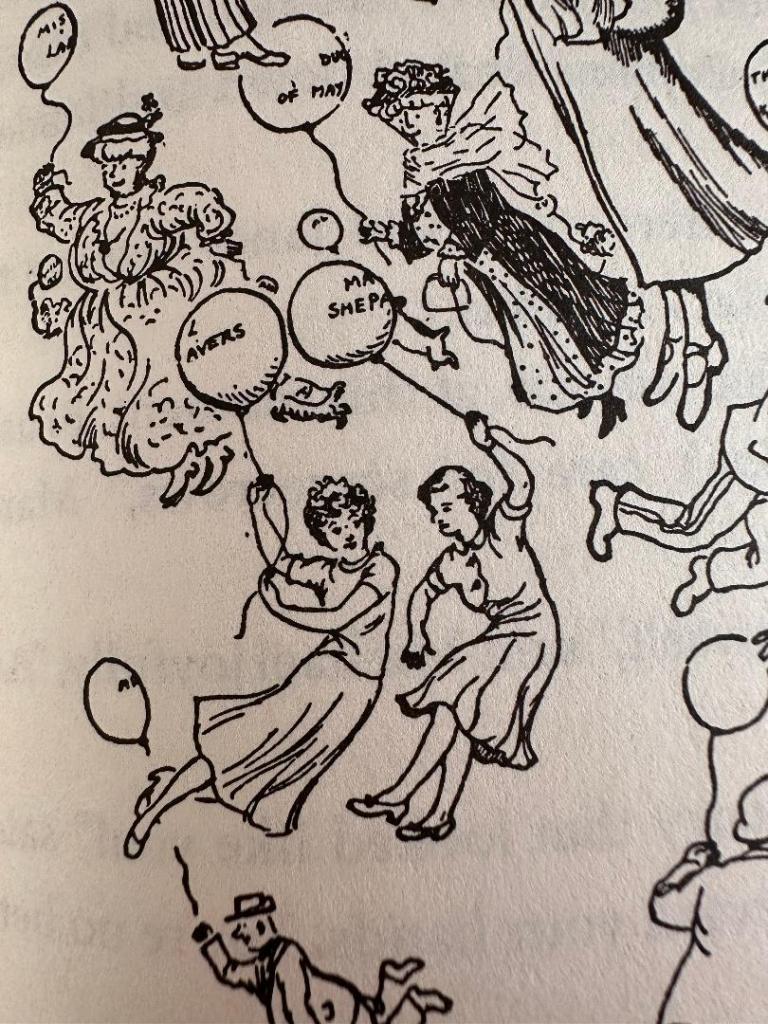

PLT: (She signs it.) I found a picture of myself in the chapter called “Balloons and Balloons.” Me and Mary Poppins and Mary Shepherd.

GM: I’ll look for it when I go home. And I should go soon. I’m flying out tonight.

PLT: Where?

GM: Dublin tonight, and Boston tomorrow.

PLT: I was at Radcliffe once, teaching. And at Smith. I loved Radcliffe. I hated Smith.

GM: Why?

PLT: A man from an American magazine called Life came to every lecture, and all the Smith girls threw themselves at him.

GM: This has been an extraordinary afternoon for me. I will never forget it. Thank you. (I kiss her.) Goodbye.

PLT: Goodbye. Write about this.

GM: Pardon—?

PLT: Write about coming here to tea.

Cheryl shows me to the door. I leave PLT sitting in the corner of the room, all eyes and smile, in a blue cardigan, knees together, hands on her knees. The big square window is now dark with dusk.

Something intriguing about the conversation: “Here I divert from my journals to insert a memory that I didn’t write down at the time. Ms. Travers elected to address me as the man who came to read the meters, and kept telling me they were out back, through that door. She seemed entirely unfazed that the meter man would arrive carrying rare copies of her hardcover books and would be conversant in arcane details of her career and work. I’ve often wondered if she wasn’t having me on.”

Reading about the man who came to read the meters made me smile. She was, most probably “having him on”. Her life quest was all about finding the meaning of life and the questions she asked in her essays were “Who are you?” and “What is man a metaphor for?” It is possible then that she was probing her guest in the manner of her spiritual teacher G.I. Gurdjieff, who used to shock and surprise his pupils with strange statements and behaviours in order to break down their habitual thought patterns and thus strip off their masks.

Now, onto my interview with Mr. Maguire and his delightful book “A Wild Winter Swan”.

LS: Is there is a possibility for a sequel of “A Wild Winter Swan”? In the ending Laura explains the swan boy’s arrival into her world in these words: “No, he has flown away from them once because he could not bear to be other than wholly human. Now he has to try the alternative. He really doesn’t have a choice. Do we.” But what if that alternative does not prove to be the solution either?

GM: I have not contemplated writing a sequel to “A Wild Winter Swan” —but I never say never with conviction. I had not contemplated writing a sequel to “Wicked”, and it was ten years before “Son of a Witch” came out. There have been five more books about my take on Oz after that one—so far.

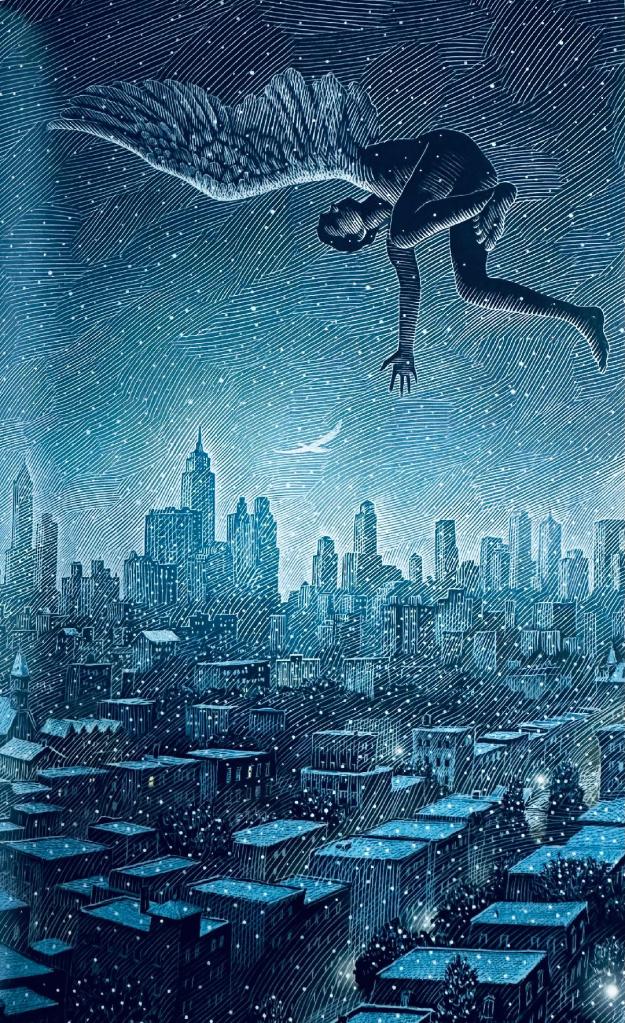

Still, in regard to “A Wild Winter Swan”, I admit there is something both sad and satisfying in the loss of a character whom one has come to love—even one who is ultimately bewildering. Not unlike, come to think of it, a certain Mary Poppins herself. I tried to leave the reader with a sense of insecurity about how and even why this boy, Hans, had landed in Laura’s life.

LS: Yes, I did wonder about that too. Did Laura somehow summon him because she herself was in a liminal state of being; suspended between the dreamland of childhood and the demands of adolescence, all in the background of the dire circumstances of her personal life? Or was it the other way around. Why did the swan boy happen to Laura?

GM: Why does anything happen to anyone? Why did Peter Pan land on the nursery windowsill of the Darling family instead of the family next door named the Oblenskys, with their fat little cousin visiting from Moscow, the one who dangled the family turtle from a third-floor window and nearly decapitated it? It just happened. Wendy’s mother told stories, after all, and Peter wanted to hear the stories.

Hans might just have landed on Laura’s windowsill by chance. Things happen in stories. On the other hand, Laura had just read the Andersen tale to those first-grade students. Then she’d come home and helped rescue a worker about to fall off Laura’s own roof. The conditions of Hans’s arrival were established in her mind by the events of the day. Maybe they helped her recognize him when it happened—or maybe it was happening largely in her mind, a dream and hope of escape and of rescue from her increasingly dire situation. (Of course, no one else saw the visitor except the cat, and there is the matter of the bloody eels, the most proof that someone else is in the house with the Ciardi family. But maybe the cat did get the eel itself, and Laura was inventing what else must have happened in the terms of the story going on in her head.)

This makes a sequel hard to position in my imagination, for in order for there to be more to Hans, I would have to be more definite about how, and what, he actually is—and that he lives outside of the story Laura is busy telling herself in her own head. And I’m not sure of that myself.

The point is, while I think that Hans is real, and so does Laura, others might not be so sure.

LS: I believe Hans to be real too, but maybe other readers will interpret the story differently. P.L. Travers said that a book is only half the writer, the other half being the reader. I wonder if you intentionally made the parallel between Laura’s inner strength and that of Elise in Andersen’s story.

Elise must knit shirts from stinging-nettle without ever saying a single word and at the risk of perishing because of it. Laura does speak in the story, but she is mute about the existence of the swan boy, and she goes about his rescue in the most secretive way despite all the challenges that his presence creates in her already troublesome situation.

I found Laura to be just as self-contained, determined and resilient as Elise in Andersen’s fairy tale. And just like in Andersen’s fairy tale, by saving the swan boy, Laura saves herself. Did you start writing the story with the end in mind, or did the narrative unfold organically in this way?

GM: When I began to write the story, I wanted Laura to be clever imaginatively but not socially—perhaps a bit backward in school. I never know how stories are going to end when I start them—that means I am uncovering the story in an organic way, as I want readers to do, too. I didn’t realize until about 2/3 of the way through the story that as Laura didn’t have the capacity—as Elise in Andersen’s story didn’t, either—to do surgery upon the swan boy and convert his swan wing to an arm, there really was only one other choice: she had to return to him a second wing, and confer upon him agency to fly away. This is also what she has to do for herself, and so I intended that the act of rescue for Hans should be synonymous, or at any rate practice, for the act of rescuing herself.

LS: Why did Laura’s grandparents choose a boarding school in Montreal as an alternative to her education? I live on the south shore of Montreal and work in the city, so naturally, this caught my interest.

GM: There is one main reason for this. As I loved books like “A Wrinkle in Time”, “Mary Poppins”, “The Wizard of Oz” and the Narnia books—among many others—I noted even then that there is a consistency of literary genre in these beloved titles. I didn’t know the word “fantasy” until I was in high school, I mean not as applied to a type of story. I called them “magic books” —books about magic (though they seemed to do magic, too, in how they made me feel!)

But I had one favorite title from childhood that was not a literary fantasy. It was the novel by Louise Fitzhugh called “Harriet the Spy”. You’ve heard of it, and perhaps you’ve read it. Harriet is a sixth-grade girl who spies on her classmates, writes things down in her journal, and intends to become a writer when she grows up. She is wildly curious and, like all children, quite naive, but she is working at increasing her bank of experiences so she can understand the world better.

In writing “A Wild Winter Swan”, I wanted to pay homage to Harriet a little. I set the story in roughly the same patch of neighborhood where Harriet lives, on the Upper East Side of New York—and in very nearly the same couple of years. (“Harriet the Spy” came out in 1964, I think, and my story takes place in 1962.) I imagined Harriet and Laura passing one another on the pavement. I didn’t want Laura to be a writer per se, as that would be too imitative, and besides Laura’s capacity to “see” and experience Hans is predicated on her simplicity, perhaps her simple-mindedness—so working arduously with words the way Harriet does would contradict Laura’s open and believing nature. Her gullibility, perhaps.

Instead, I had Laura “think” stories—narrate her own experiences in her head as she would write them—if she were a writer. She is not shy of imagination and thoughtfulness, after all—or of imaginative sympathy—but she is not academically robust, either. This method allowed me to have Laura comment on her own experiences but only in her head. It’s another proof that she lives in her mind, and therefore another hint that the incidents with Hans may be self-generated. (You might say she is having a schizoidal break, unable to separate between reality and fantasy. I mean some might say that. I wouldn’t.)

In “Harriet the Spy”, the child’s beloved governess leaves the household about halfway through the novel to get married. She tells Harriet she is going to move with her beau to Montreal. To Harriet, Montreal seems as far away as the moon. “Mon-tre-ALLLL?” she wails when she hears the plan. My threat of sending Laura to Montreal was a quiet tip of the hat to Louise Fitzhugh.

I like Montreal, though. My big sister, who was a little like Laura in 1962, grew up and married a Canadian man and spent all her adult life in Montreal, Quebec, and Toronto, and is now retired as a grandmother in Ontario. So, growing up in Albany NY, Montreal was to me a place of warmth and attraction, and I liked, and like, visiting.

LS: In your interview by Kristen McDermott, you say that “Magic helps the young reader skip over some of this as-yet-imponderable mysteries and supplies instead a set of inchoate influences that organize a mystifying world to the young mind.” What role and significance does magic hold in the world of adult readers?

GM: At this point in my life I think fantasy is largely a gift for the young. I don’t seek it out to read as an adult (though I do love to return to books I loved as a child). There are some exceptions. The Philip Pullman novels come close to matching, in moral seriousness, what Ursula Le Guin managed in her Earthsea books. But I think a sort of disservice has been done to the reading of fantasy by the technical marvels of CGI in the film industry. When virtually anything can be pictured, and pictured convincingly, thanks to the wizardry of computer animation etc., then the thrill of reading of something impossible happening on the page is somewhat demoted.

The strength of fantasy in the lives of children is still potent, though. Fantasy still has power to charm because children have not yet finished pacing off the dimensions of the structure of reality. In fantasy, they are playing with “what might be” without being entirely sure. Of course once they get to the age of five, most children realize that humans don’t fly, and can’t fly, and they won’t—and yet they can fly in their dreams! So what’s that all about? And there are other enchantments (the thrill of romance and sex, when they get there) that will seem to open up the world to them in ways they couldn’t have anticipated a year or two earlier.

While adults, having convinced themselves that they’ve (largely) got the measure of reality, must approach fantasy in literature with a different expectation. Indulging in that literary art is a bit nostalgic, perhaps; it can more easily be read as metaphoric; in any case fantasy is at least diverting and a consolation, allowing one to turn away from the vicissitudes of our increasingly hostile and dangerous life on this planet. But as a rule, fantasy literature for adults can no longer tempt as a possible alternative construction to reality that we might someday find our way into embracing—as Laura does, in my story. That magic casement is closed. Peter Pan knows it, and so even does Mary Poppins.