Dear Reader,

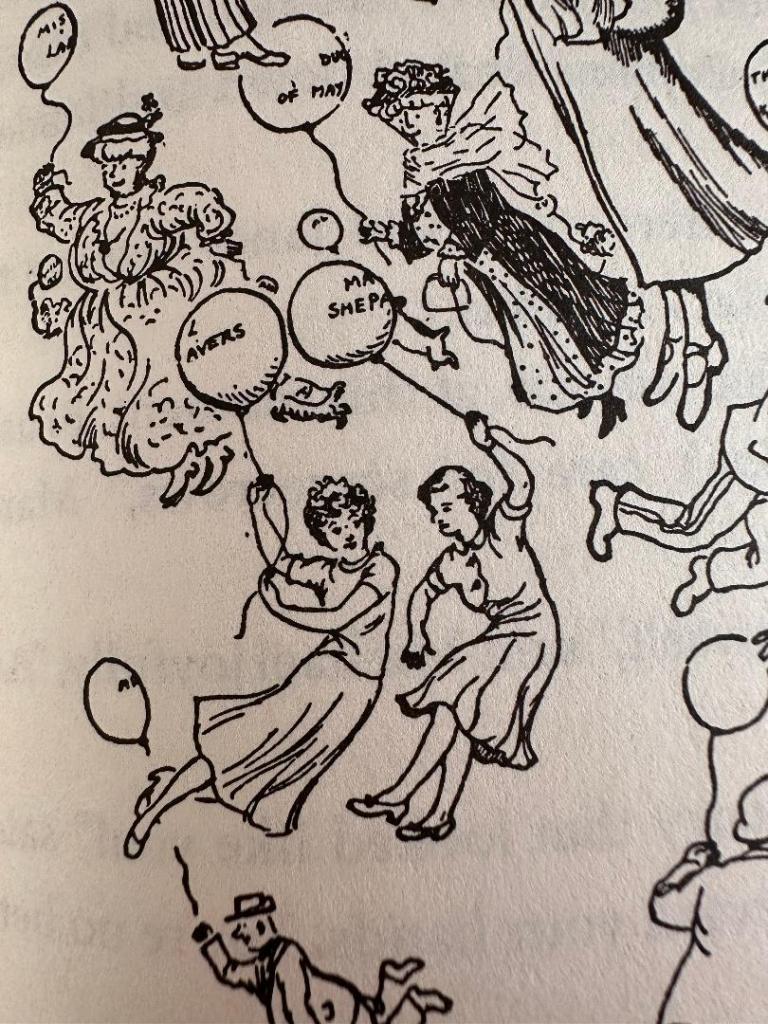

This post continues the story about my first Mary Poppins–themed trip to London with my daughter in the summer of 2023. In last month’s post, I shared our visit to P. L. Travers’s former homes at 50 Smith Street and 29 Shawfield Street in Chelsea. If you haven’t read it yet, you can find it here.

In this blog post, we will visit St Paul’s Cathedral, stroll through Poppin’s Court near Fleet Street, shop for parrot-headed umbrellas at James Smith & Sons and admire the Mary Poppins statue in Leicester Square Gardens.

St Paul Cathedral, London

If you find yourself in London, a visit to St Paul’s Cathedral is, in my humble opinion, an absolute must. Its grandeur is astonishing—from the soaring colonnades to the magnificent domed ceiling—and the vast interior, adorned with intricate mosaics, takes your breath away the moment you step inside.

This iconic landmark was especially dear to P.L. Travers, who featured it not only in The Bird Woman chapter of her first Mary Poppins book, but also in her later 1975 Christmas tale The Fox at the Manger. I’ve explored this story in detail on the blog—you can read more in: A Christmas Story by Pamela L. Travers, The Nativity Reimagined by the Author of Mary Poppins, The Fox at the Manger (Part I) and (Part II).

In The Bird Woman, Mary Poppins takes the Banks children to visit their father who works at the bank, where he, as described in the very first Mary Poppins story, East Wind, “sat on a large chair in front of a large desk and made money. All day long he worked, cutting out pennies and shillings and half-crowns and threepenny-bits.”

I wish the idea of looking up banks around St Paul’s Cathedral had occurred to me while I was there, but it didn’t—so this will have to go on my list for my next trip to London. I’m talking about the bank where I believe P. L. Travers imagined Mr. Banks working: the Ludgate Hill branch of the City Bank at 45–47 Ludgate Hill, which, according to Memoirs of a Metro Girl, is now a wine bar.

The picture above was taken by Metro Girl and is shared here with her permission 🙂

How do I know this was the bank P. L. Travers had in mind when she wrote “The Bird Woman”? Because she writes: ‘They were walking up Ludgate Hill on the way to pay a visit to Mr. Banks in the City.’

In The Bird Woman we learn that Mr. Banks is entirely absorbed in material pursuits and has no time for small pleasures. But we can hardly blame him—he is the sole provider for his ever-growing family (by the second book in the series, the Banks family counts five children). Hoping to offer him a rare moment of joy and respite, Mary Poppins and the children plan an outing for tea and Shortbread Fingers. Yet Jane and Michael are far more excited by the possibility of meeting the Bird Woman and her pigeons outside St Paul’s Cathedral than by the promised tea and shortbread.

Because of the sharp contrast between the Bird Woman’s quiet act of feeding the birds and Mr. Banks’s worldly occupation, The Bird Woman takes on a distinctly spiritual undertone for the adult reader. The doves, traditionally associated with the Holy Spirit in Christianity, serve here as a visual metaphor for the nourishment of the soul. Clearly, P.L. Travers is concerned with our human struggle to balance material responsibilities with the quest for spiritual fulfilment.

Yet for carefree Jane and Michael, the Bird Woman and her doves are simply companions to delight in and play with. For them, the magic of the day is found in this gentle, enchanting encounter—an experience that carries them beyond the ordinary and into a realm of wonder.

I love how P. L. Travers conveys Jane and Michael’s understanding of the doves, while at the same time revealing her own gift for remembering how to see the world through the eyes of the child she once was.

“There were fussy and chatty grey doves like Grand-mothers; and brown, rough-voiced pigeons like Uncles; and grey, cackling, no-I’ve-no-money-today pigeons like Fathers. And the silly, anxious, soft blue doves were like Mothers. That’s what Jane and Michael thought, anyway.”

Jane and Michael (and probably P.L. Travers) relate to the animal world far more naturally—and kindlier—than most adults. To them, the birds are not pests but companions, each a living being with its own character. We, on the other hand, tend to brush past pigeons and doves as if they were mere annoyances, hardly pausing to see them at all—too busy rushing for the train or speeding down the highway, intent on our own version of cutting pennies and shillings.

I experienced my own version of feeding the birds—not at St. Paul’s Cathedral, but in St. James’s Park. While we were there, a little girl, slightly older than Jane and Michael Banks, had a bag full of seeds. She was not only feeding the birds but also offering seeds to passersby who, like me, wanted to join in the experience. It was deeply touching, and here is a short clip of me feeding the birds.

Many of the characters in the Mary Poppins stories—if not all—have their roots in the real-life experiences and encounters of P.L. Travers. She rarely revealed these inspirations openly, though hints occasionally surfaced in interviews she gave throughout her long writing career.

I have never come across an interview in which P. L. Travers spoke about the origin of the Bird Woman. However, I did find an old picture of a man standing outside St Paul’s, his arms and shoulders alive with pigeons as he feeds them. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, while working as a freelance journalist near Fleet Street, P. L. Travers often passed by St Paul’s Cathedral, and I can’t help but wonder whether this man might have been the true inspiration behind the Bird Woman.

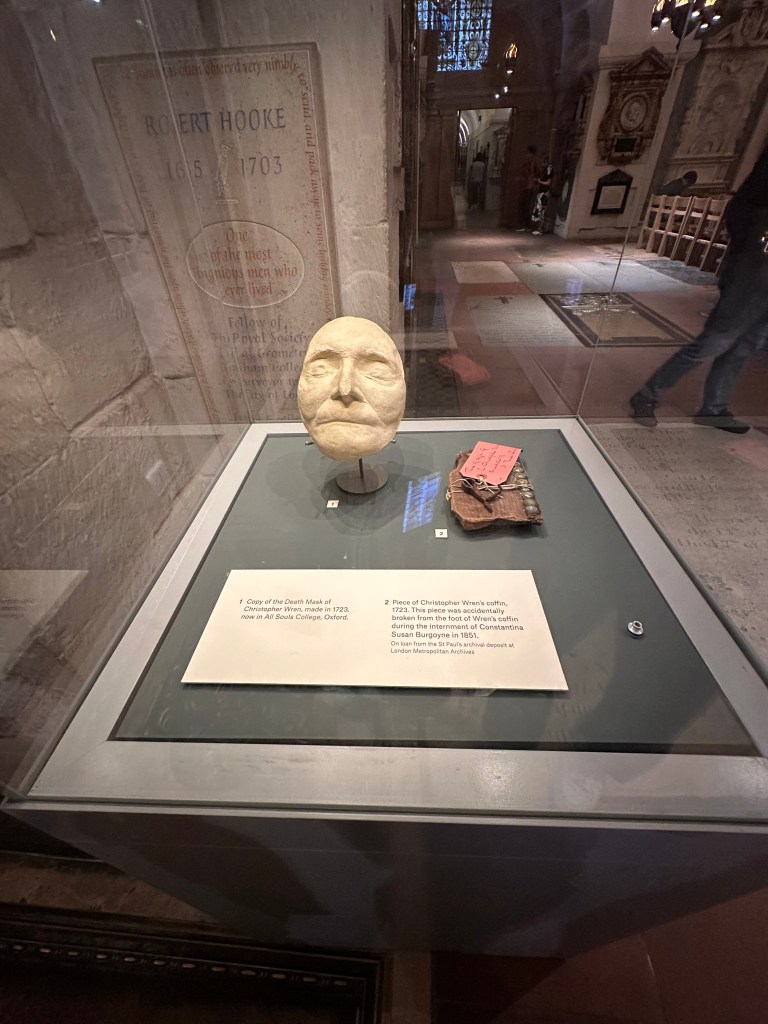

St Paul’s Cathedral, as P.L. Travers writes in The Bird Woman, was built long ago by “A man with a bird’s name. Wren it was, but he was no relation to Jenny.” That man, of course, was Sir Christopher Wren, England’s most celebrated architect of his day. When my daughter and I visited St Paul’s Cathedral in the summer of 2023, we saw a lovely exhibit inside about Sir Christopher Wren and the reconstruction of the building after the Great Fire of London in 1666.

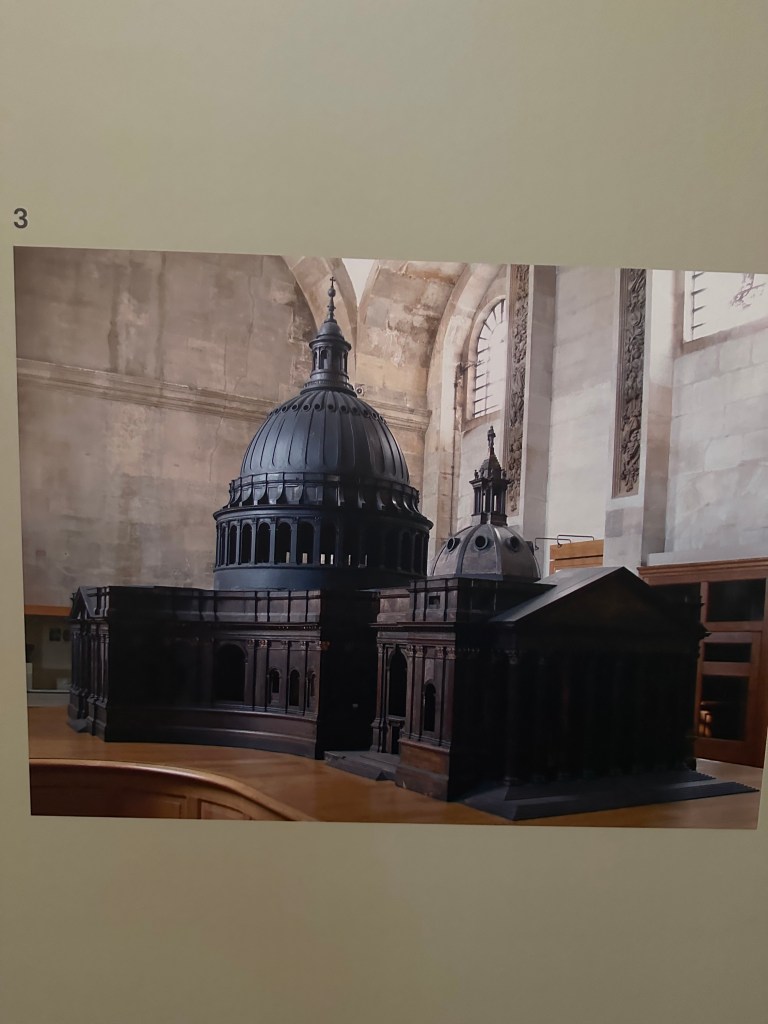

Wren designed the Great Model of the cathedral in 1672–73. The version you see in the picture below was executed by William Cleere and a team of thirteen joiners. This design differed from the original in style, evolving from the “Greek Cross” plan by extending the nave and adding a domed bell tower.

King Charles II, who awarded the reconstruction contract to Wren, requested a slight modification: the domed bell tower had to be replaced with a traditional spire. But Wren was not a man easily discouraged. Once the plans were approved and the contract signed, and construction was well under way, he discovered a loophole in the fine print: it permitted ornamental rather than essential changes. So, he made his alterations accordingly.

St Paul’s Cathedral is also Wren’s final resting place. Below is a photo of a copy of Wren’s death mask—the original is preserved at All Souls College in Oxford. A little morbid, perhaps, yet also a fascinating human attempt at transcending death.

Now who is Jenny Wren? What did P.L. Travers meant by saying that Wren was not related to Jenny? The reference is a pun woven by P.L. Travers—one I had completely missed, since English folklore and nursery rhymes were not part of my upbringing. For those who may also be unfamiliar: the wren, a tiny brown bird, was affectionately called “Jenny Wren” in English tradition. She appears in old songs and nursery rhymes, often paired with Robin Redbreast as husband and wife.

Children in P.L. Travers’s time would have instantly recognized “Jenny Wren” as shorthand for the little wren, and the playful wordplay would have delighted them. It signals to young readers that the world is whimsical, alive with hidden connections. The pun weaves together architecture (Wren), folklore (Jenny Wren), and the story’s imagery of birds and the mystical Bird Woman—perfect for a chapter set at St. Paul’s amid flocks of pigeons.

And for adult readers, there’s yet another layer: an echo of Dickens. Jenny Wren is also a character in Our Mutual Friend. That reference escaped me as well, but this Dickens novel has now joined my ever-expanding TBR list.

Poppin’s Court

Not far from St Paul’s Cathedral, just off Fleet Street, you will come across a narrow lane called Poppin’s Court. When P.L. Travers first came to London she worked as a free-lance journalist on a street near Fleet Street and she must have passed by Poppin’s Court on her way to St Paul’s Cathedral, and it is, as her friend Brian Sibley wrote, possible that this is how she came up with the idea for the name of her famous nanny.

Back in 2023, when my daughter and I visited Poppin’s Court, there was a Poppins Café, which may still be there. Sadly (for me), it had nothing to do with Mary Poppins. I would have loved to visit a Mary Poppins–inspired tea room based on the books.

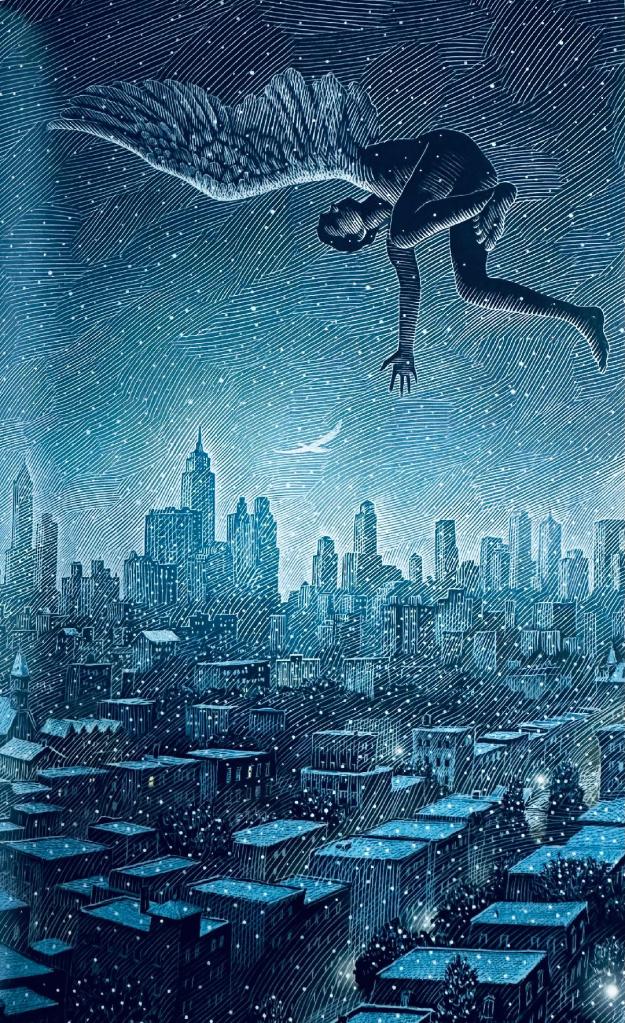

Leicester Square Gardens

If you have time, be sure to stop by Leicester Square, where you’ll find several statues capturing iconic movie moments from different decades since the 1920s — and of course, one of them is Mary Poppins. Although the Mary Poppins statue in Leicester Square celebrates the film character rather than the one from the books, I couldn’t resist trying to ‘fly away’ on her umbrella.

Since this Mary Poppins statue was created many years after P.L. Travers’s death, we can only guess what she might have thought of it. What we do know is that she once wished for a statue of her character in London—though her dream location was Kensington Gardens. I will tell you more about that in a future post on this blog.

James Smith & Sons Umbrellas

If you want to get a parrot-headed umbrella like Mary Poppins’, you should definitely visit James Smith & Sons Umbrellas, a tiny shop founded back in 1830. I have no idea whether P.L. Travers knew about this shop or if she ever visited it. According to her own account, the inspiration for the parrot-headed umbrella came from a childhood memory of a servant’s umbrella in the Travers household in Australia (and maybe by something else, which I also plan to tell you about in a future post). But whether or not P. L. Travers ever visited this shop, I thoroughly enjoyed our own visit — dampened only by the scaffolding on the facade, which was under renovation.

Here is a picture of a parrot-headed umbrella standing proudly beside another famous fictional character. I was tempted to purchase both, but the price tag quickly discouraged me. But two years later I am still thinking about this parrot headed umbrella …

That’s it for now—thank you for reading! If this post brought you a little joy, just click the subscribe button in the bottom-right corner of your screen and join me for the next stop in my Mary Poppins adventures through London and beyond. You can also follow along on Facebook and Instagram for more glimpses into the magical world of Mary Poppins and P.L. Travers.

Until next time, take care and be well.