Dear Reader,

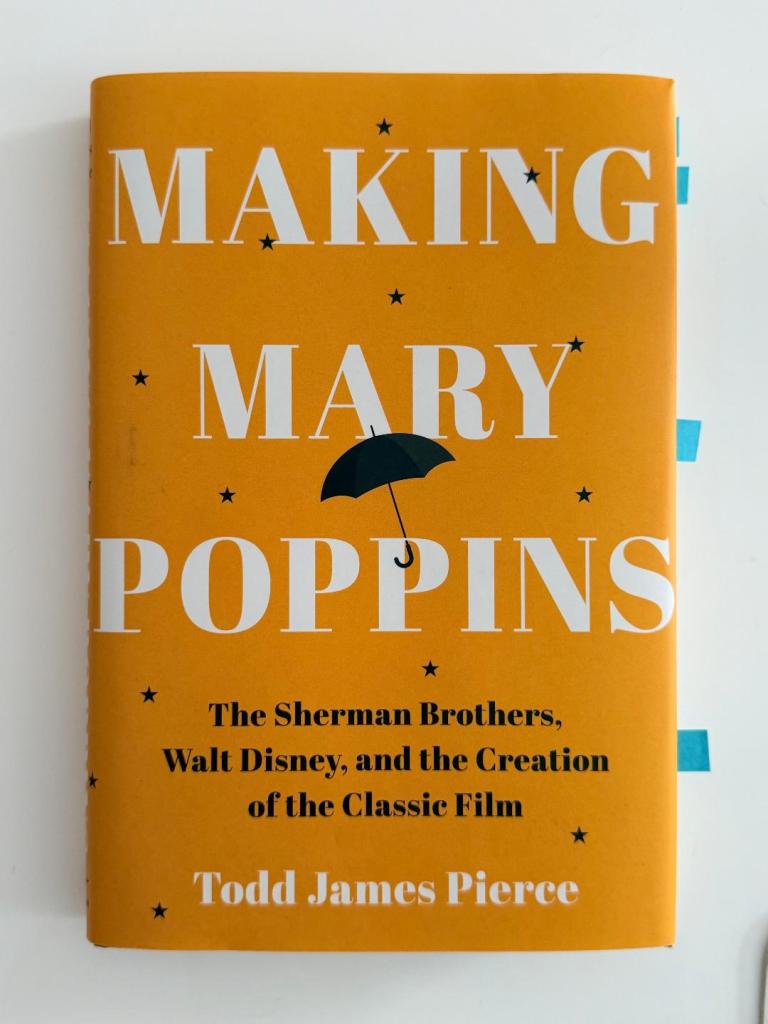

Did you know that a new book about Mary Poppins was released last October, titled Making Mary Poppins: The Sherman Brothers, Walt Disney, and the Creation of the Classic Film by Todd James Pierce? The book explores the making of the 1964 film starring Julie Andrews as Mary Poppins. While documentaries and other accounts of the making of the film already exist, this book shifts the focus to the personal and professional lives of the Sherman brothers. Rather than centring solely on the movie, the first part of the book traces their family background, beginning with their father and early childhoods, and follows their long struggle to succeed in the musical industry, culminating in their breakthrough as the songwriters behind Mary Poppins.

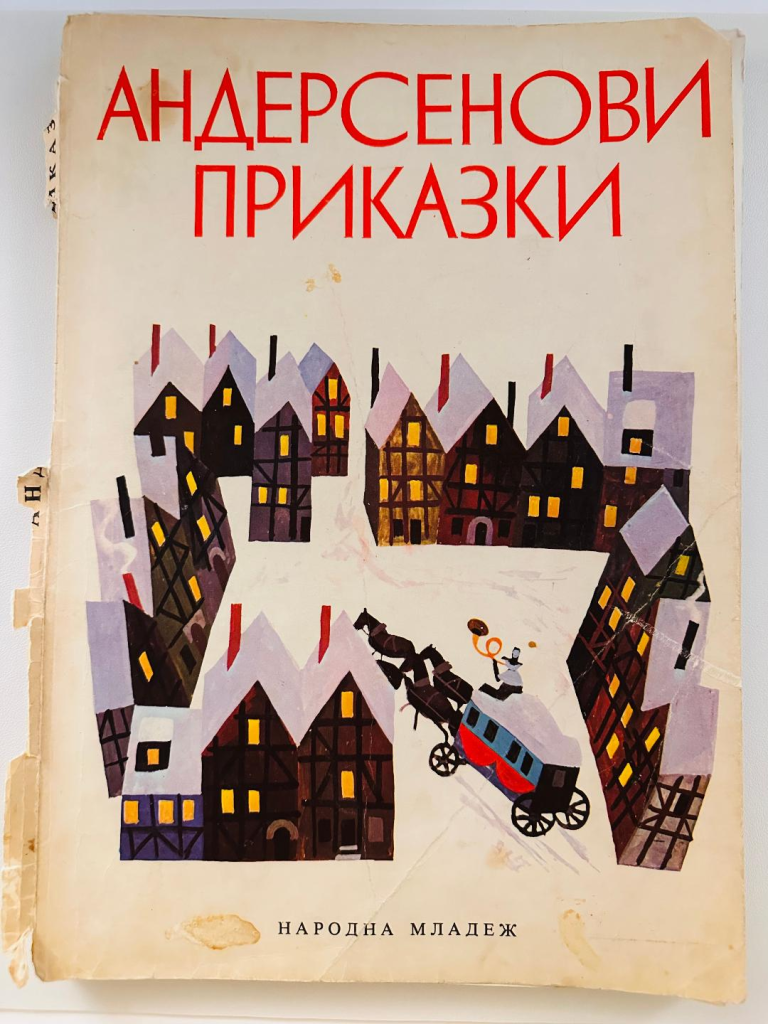

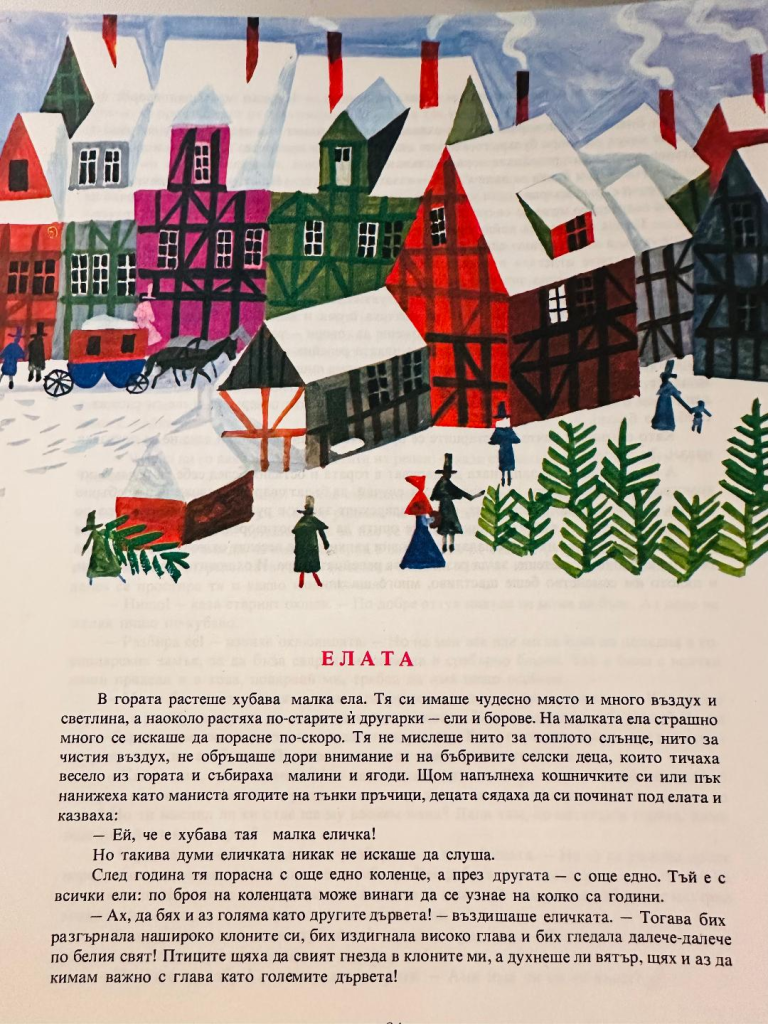

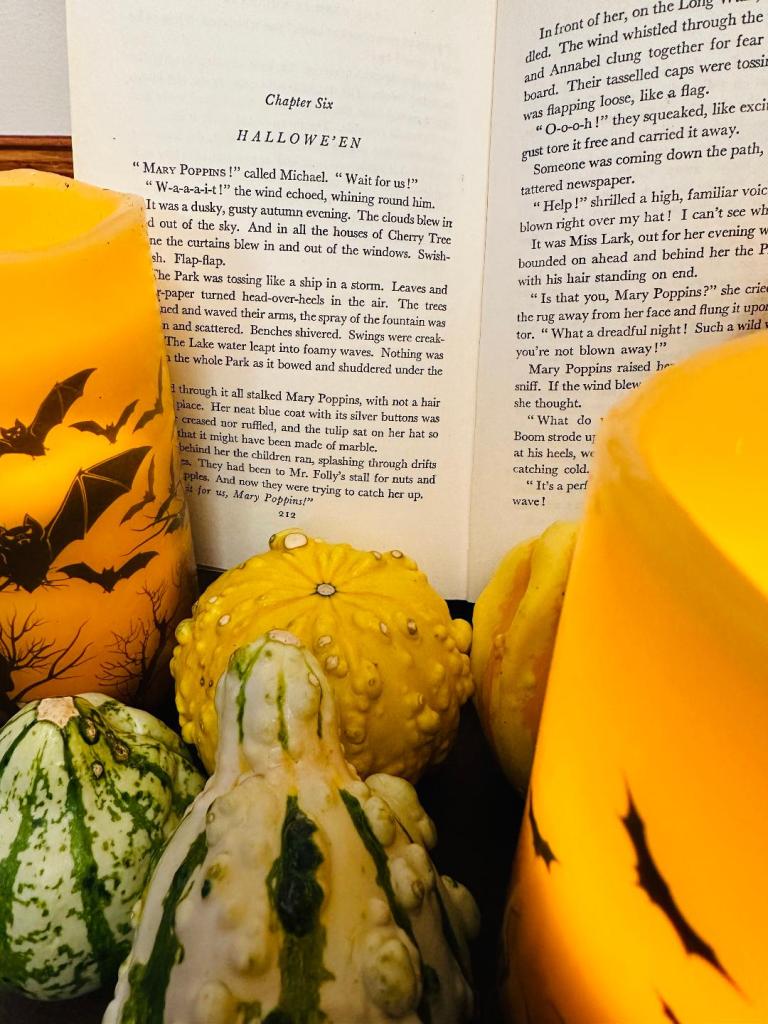

I am a fan of the Mary Poppins books by P. L. Travers, as they are where I first encountered Mary Poppins as a child. I only discovered the existence of the film in 2015, after reading Mary Poppins She Wrote by Valerie Lawson, the first written biography of P. L. Travers. This may sound strange, but the fact is that I spent my early childhood in Bulgaria during the Cold War. Disney films were viewed as products of American capitalist culture and, as such, did not make it behind the Iron Curtain.

The political regime of that period viewed Disney as promoting bourgeois values and glorifying individualism and consumerism. Because the state conceived of itself as the guardian of children’s impressionable minds, it sought not only to shield them from harmful bourgeois influence but also to guide them toward socialist values, shaping them into future workers and citizens bound by a moral duty to serve society.

How, then, you may ask, was it possible for the Mary Poppins books to be translated into Bulgarian and made available to children? One plausible explanation is that reading was regarded primarily as an educational practice rather than a form of mass entertainment. Furthermore, the books may also have appeared less overtly Western or glamorous in tone.

In the literary version, Mary Poppins is markedly stricter, colder, and more ambiguous than the character portrayed by Julie Andrews. The original Mary Poppins is authoritarian, ironic, and emotionally distant. In addition, the stories can readily be interpreted as conveying lessons in discipline, hierarchy, and moral correction, all qualities that stand in sharp contrast to the film’s lavish spectacle.

Luckily for my childhood self, and for other young readers of that time, Western children’s literature appears to have been tolerated so long as the stories lacked explicit political content and were not oriented toward consumption. Other children’s classics, such as Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Peter Pan, Peter Rabbit, and Winnie-the-Pooh, similarly slipped past communist censorship and quietly beguiled our imaginations. At the time, I was, of course, entirely oblivious to the broader social and political context in which I encountered these books.

I liked the Mary Poppins film. I admit that it is difficult not to like it. It is a visual and auditory delight, a feast for the senses. Still, it is not the Mary Poppins of my childhood, nor the one I rediscovered as an adult. It is an entirely different artistic creation. The screen version, entertaining as it may be, lacks the depth and mystery of the Mary Poppins found in the books. I am always struck by the comments of adult readers who, as children, first encountered the character through the film. They often express the opposite reaction, largely because they are surprised by the stark difference in the personality of the literary Mary Poppins.

In the books, Mary Poppins is harsh, cold, and not given to explanation. This never troubled me as a child. From the very first chapter, I was convinced that her severity was a kind of pretence, that she only appeared strict. The contrast between her outward demeanour and the inner self I sensed made her all the more compelling and rendered the magical adventures she led the Banks children on even more wondrous. I suspect that other children reading the books felt much the same.

Her contrariness does not trouble me now either. Instead, it makes her more human, precisely because of her ambiguity. She may possess magic, she may be the Great Oddity or the Great Exception, she may even have reached a higher level of consciousness, for all we know, yet she remains unmistakably human. Are we not all a little more ambiguous than we care to admit?

Despite my allegiance to the original Mary Poppins, I felt compelled to read Making Mary Poppins, if only to see whether the incident involving P. L. Travers, Walt Disney, and the Sherman Brothers might be portrayed with greater nuance. The title of the chapter devoted to this encounter, “The Trouble with Travers,” quickly dispelled that hope. A look at the Notes section at the end of the book suggests that Pierce relies heavily on Valerie Lawson’s biography of P. L. Travers and on the Sherman brothers’ own testimonies, while demonstrating limited engagement with P. L. Travers as a writer and spiritual thinker.

I would have welcomed a discussion of the cultural differences between P. L. Travers and Disney, or an exploration of the inner conflict she most likely experienced in the process of relinquishing control over her creative vision of Mary Poppins. Instead, the reader is once again invited to pick sides in a simplified clash of two creative visions. Worse still, the narrative encourages us to commiserate with the hardworking Sherman brothers, finally given their chance, while casting P. L. Travers as the obstructive and unreasonable figure standing in the way of their great success.

But why pick sides in this artistic conflict? Why not simply observe it in all its complexity? Yes, P. L. Travers did not follow the same logic as the Sherman brothers or Disney, but there was still logic behind her actions and her words. She was not as irrational or contrary as the cultural establishment has long been inclined to portray her.

Let us turn the tables here. The prevailing story has long favoured Disney’s version as generous, creative, and life affirming, while casting P. L. Travers as obstructive, eccentric, or emotionally difficult. When someone’s behaviour is labelled this way, it becomes easy to dismiss. It suggests that there is nothing to engage with intellectually, only a difficult personality to endure. More disheartening still is that women are often, even today, dismissed as overly emotional and difficult in situations where they are simply affirming their opinions and values.

How about we question those assumptions? We must recognise how power, gender, and cultural authority shape which voices are celebrated and which are marginalised. The loudest voice is not always the truest. We need to restore intellectual and moral complexity to a figure whose resistance was grounded not in whim, but in a coherent artistic vision and a deep sense of responsibility toward her work.

P. L. Travers was shaped by a cultural background that valued myth, folklore, and symbolic meaning. Her imagination was steeped in fairy tales, Celtic myth, and archetypal storytelling, where ambiguity is not a flaw but a feature. She wrote, “Fairy tale is at once the pattern of man and the chart for his journey.”

Through her engagement with esoteric traditions and thinkers such as George W. Russell, W. B. Yeats, and Gurdjieff, she believed stories could transmit moral and spiritual truths indirectly. For her, meaning was not something that needed to be explained but something to be experienced, because real wisdom is achieved through lived experience.

The Sherman Brothers, on the other hand, emerged from an American popular entertainment background. Their songs express feelings directly. Joy is declared, not hinted at. There is little mystery, because the goal is inclusion rather than initiation. Their background aligned naturally with Disney’s vision of family friendly, emotionally transparent storytelling.

The artistic conflict, then, was not merely about temperamental differences. It was a clash of cultural assumptions. P. L. Travers believed stories should challenge and unsettle. The Sherman brothers and Disney believed stories should reassure and delight.

Because of these differing assumptions, interpretations of the character of Mary Poppins diverged. P. L. Travers openly articulated her belief that the true magic in her books lay in the ability to engage successfully with ordinary life. To grasp her position, one must approach the stories as allegories. The Sherman Brothers, by contrast, understood Mary Poppins as a figure who brings magic into ordinary life, which implicitly assumes that ordinary life itself lacks magic. For P. L. Travers, the opposite was true. Ordinary life already contained magic. It was the springboard from which magic emerged.

Even before she met Disney, she disagreed with the way he altered beloved fairy tales, which helps explain why she refused to sell the rights to Mary Poppins for nearly twenty years. Interestingly, her views on Disney’s work were also shared by two other British writers. J. R. R. Tolkien and C. S. Lewis likewise believed that fairy tales and fantastical stories carry meaning and convey truths about life. Both disliked Disney’s animated film Snow White, and so did P. L. Travers. It becomes easier, then, to understand why it was extremely difficult for her to see her own creation as merely a vessel for entertainment, no matter how enticing and successful that vessel might be.

Beyond cultural differences and divergent views on the purpose of storytelling, another important distinction separated the Disney team from P. L. Travers. The Disney team operated comfortably within the world of entertainment and the logic of commercial success. Creating for money was not only acceptable; it was the point. The more successful the production, the better.

P. L. Travers approached money differently. She was not indifferent to it, but she did not see it as the primary measure of value. For her, money always carried a spiritual dimension. When she was young, her literary mentor George William Russell, known as AE, introduced her to the idea of the poet’s vow of poverty. This did not mean literal destitution. As she later explained to Brian Sibley, “It didn’t mean that if you were offered $100,000 you would refuse it. But it meant that you would not be attached to it. You didn’t even need to give it away but you wouldn’t live by it.” The principle was inner detachment. Money must not become the master of the work.

Years later, her spiritual teacher George Gurdjieff articulated a related but more demanding position. The material question was not whether one should have money, but whether one could earn, manage, and use it without guilt, vanity, or self deception, and without allowing it to define one’s inner work. Money, in this view, was a force that revealed character.

By the early 1960s, P. L. Travers was facing practical pressures. Sales of the Mary Poppins books had slowed. She was ageing. Her adoptive son, Camillus, had discovered that she was not his biological mother, a revelation that strained their relationship. It is not unreasonable to assume that financial security, and what she might eventually leave behind, weighed on her mind.

At the same time, she felt the adaptation threatened her artistic vision. In a conversation with Janet Graham shortly after the film’s release, she explained: “You must remember that an author’s idea is very precious to him, it’s like a child to a mother. So that if somebody comes along and turns it into a fair haired child when it is dark, or gives it four legs instead of two, he can’t be utterly pleased, even though the effect is something very gorgeous and splendid.”

This statement clarifies much of her resistance. From the outside, her behaviour appeared obstinate, even irrational. According to accounts reported by Pierce in Making Mary Poppins, many people working at the studio found it strange that she would stand in the way of a lavish film adaptation. Yet from her perspective, taking the money while her creation was altered beyond recognition carried a far greater cost, the quiet betrayal of her own artistic vision.

In the end, practical considerations prevailed. But her ambivalence never disappeared. When asked about Logan Pearsall Smith’s assertion that “There are few sorrows, however poignant, in which a good income is of no avail,” she replied with her usual wit, “I should think that that was true, at any rate externally; at least you could go to the movies and forget it for a time.” Her remark acknowledges money’s utility while quietly denying its power to resolve deeper conflicts.

The encounter between the Disney team and P. L. Travers is compelling precisely because neither position is illegitimate. They were operating from fundamentally different premises. One measured success in entertainment, originality, and revenue. The other measured it in loyalty to an inner vision.

We are often tempted to reduce complex conflicts to a clash between heroes and villains because it simplifies uncertainty and soothes our anxiety. Yet adult life, and especially artistic life, rarely conforms to such black and white thinking. Two positions can be internally coherent and still irreconcilable, as in the making of Mary Poppins.

Thank you for reading. If this story resonated with you, I invite you to subscribe to The Mary Poppins Effect, where I share reflections on Mary Poppins, her connections to other literary worlds, and my musings on books and the quiet magic of childhood.

Until next time, be well.

Lina