The last two posts on this blog (analysis of the story of “Ah Wong” published in 1943 and analysis of the story of “Johnny Delaney” published in 1944) revealed Pamela L. Travers’s religious upbringing and the signs of her losing her religion after the early and sudden death of her father. These two stories were written during Pamela L. Travers’s war time evacuation to the United States, and as Christmas gifts for her friends; thus published privately.

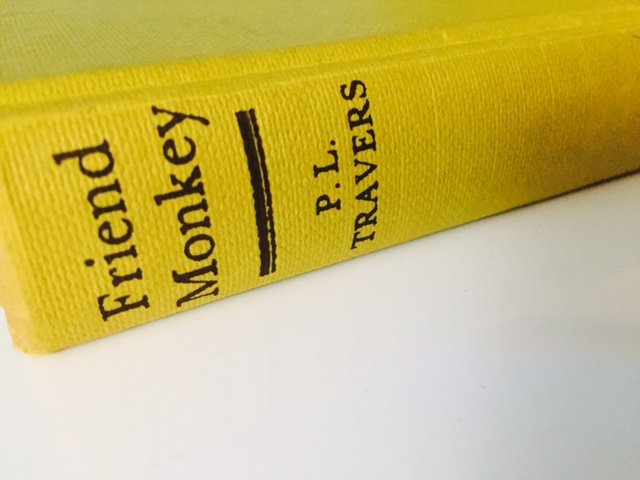

The story of “The Fox at the Manger,” which is the subject of this week’s post, was published at large in 1963, almost twenty years after the end of the war and in my opinion, it expresses the same sentiment of rejection of the main-stream Christianity and the spiritual void experienced by Pamela L. Travers as the stories of “Ah Wong” and “Johnny Delaney“.

The “Fox at the Manger” is an account of the first Christmas service at St. Paul’s cathedral in post-war London when people were just beginning to settle back into their normal lives. The narrator (who is obviously Pamela L. Travers) takes three boys to the Christmas service. One of the little boys is dear to her heart and is obviously her son Camillus. By the way, the story is dedicated “To C. to remind him of his childhood.”

Each of the boys are bringing one of their favorite toys with the intention of offering them as presents for the poor children in London. But when the moment comes for the boys to part with their precious possessions, they remorselessly change their minds. To this, the narrator (Pamela L. Travers) wisely concludes “A gift must come from the heart or nowhere.”

Obviously, the story is about giving and about loss. As Patricia Demers writes in her book, “P.L. Travers,” “The Fox at the Manger” is “an affective meditation on gift giving.” But there are also other layers woven into the story which deserve closer exploration. So, let’s explore them.

The story begins with, and is wrapped around, the Christmas carol of the Friendly Beast.

Carol of the friendly beast

(Here sang by Peter, Paul and Mary)

Jesus, our brother, strong and good

Was humbly born in stable rude

And the friendly beasts around him stood

Jesus, our brother, kind and good.

I, said the donkey, shaggy and brown,

Carried his mother uphill and down,

I carried her safe to Bethlehem town,

I, said the donkey, shaggy and brown.

I, said the cow, all white and red,

Gave him manger for his bed,

I gave him my hay to pillow his head,

I, said the cow, all white and red.

I, said the sheep with curly horn,

Gave him my wool to keep him warm,

He wore my coat on Christmas morn,

I, said the sheep with curly horn.

I, said the dove, in the rafters high,

Cooed him to sleep with a lullaby,

We cooed him to sleep, my mate and I,

I, said the dove in the rafters high.

Thus, every beast by some good spell

In the stable dark was glad to tell

Of the gift he gave Immanuel

Of the gift he gave Immanuel.

As a side note, I learned that this song probably originated in 12th-century France and was sung during the Fete de l’Ane (Festival of the Ass or Donkey), and the focus was the flight into Egypt by the Holy Family. At some point over the centuries, the scene shifted from the flight into Egypt to the journey to Bethlehem. Robert Davis (1881-1950) is attributed with writing the English words, probably in the 1920s.

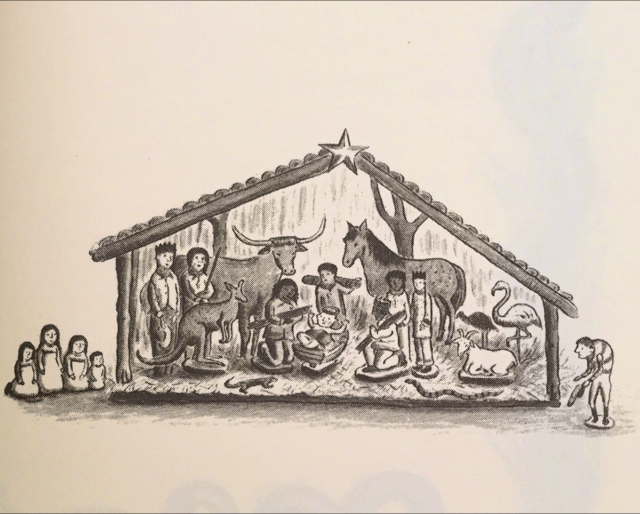

And now back to the story. The children in the story prove themselves to be keen observers. When the Church choir sings “I, said the donkey, shabby and brown” one of the boys remarks that the donkey in the Nativity scene is actually quite grey and smooth. Then another boy candidly demands: “Why, he asked, are they (the clergymen) wearing nightgowns? They look like Wee Willie Winkie.”

Now, I didn’t know who Wee Willie Winkie was, so for those who may be ignorant of the character, here is a link to Wikipedia. Basically, Wee Willie Winkie is a character from a nursery rhyme (Pamela loved nursery rhymes) dressed in a night-gown and running around town tapping on windows and reminding children to go to bed. Therefore, it is not exactly a dignifying comparison for the clergymen.

Although seemingly embarrassed by the attention from the congregation caused by the children’s comments, the narrator does not find the words to contradict them. She herself wonders, looking at the bishop lip-syncing the carol, “through what town of the mind this paunchy Wee Willie Winkie was running.” And then, to continue with her own meditation on the nativity scene:

The rose-bloom faces of the kings gave no hint of the discipline, the labors, that must surely be the lot of any group of Magi.

And what disappoints her the most, is the absence of a black sheep amongst the white lambs:

And I dearly wanted a black lamb. For without him, where are the ninety and nine? Flocks, like families, have need of their black sheep he carries their sorrow for them. He is the other side of their whiteness. Does anybody understand I wandered, that a crib without a black lamb is an incomplete statement?

This passage in the story reminded me of another one of Pamela L. Travers’s essays published in Parabola in 1965, “The Black Sheep:”

What was a black sheep, I asked myself. Obviously, in the general view, one full of iniquity. If so, might I not be one myself, in spite of the tireless efforts of parents, teachers and friends.

The expressed feelings of not belonging to a tribe and being somewhat flawed are so obvious and ever recurring in her writings; even in the stories of Mary Poppins. But that will be explored at another time on this blog.

So, from the dialogues between the boys and the narrator, and the narrator’s own reflections of the religious service, one can easily deduce Pamela L. Travers’s general dissatisfaction with the religious concepts from her childhood. The worship rituals are portrayed in the story as a thoughtless mimic and mindless repetitions by some slightly ridiculous clergymen. Clearly, Christianity did not provide answers to her questions nor did its teachings reflect what she perceived as being the truth.

So again, as in the previous stories, we can trace Pamela L. Travers’s rejection of the Christian religious beliefs. Yet, at the same time, the reader can feel a deep sense of her spiritual sensibility. She writes about the passage of time, which is associated to the flow of life, as something deeply mysterious and undisturbed by human actions:

Whenever the bombs fell in London, reinforcements in the shape of sycamore, rose-bay willow, and fern came to fill the gaps. …. What had been here- some stately office? A bank? A merchant’s hall? And before that, what? I wondered. If it is true the print and form of things remains forever, as they say invulnerable and invisible -surely these children were dancing now through long forgotten board meetings, and shades of accountants, lawyers, clerks. Or if one went back further, through the flames of the Fire in London in 1666. Further still, the marble floor would be mud and marshland and all around us brontozors; and beyond that we would whirl in lava, turning fierily through the air, nothing but elements.

Contrariwise, would not the City lords to come, in rooms that would rise from this fern and rubble start up in astonishment at the fancied sight of willow-herb breaking through the carpet. And old cashiers scratch their heads, wondering if they were out of their wits or whether they had really seen three boys run through the cash desk? Are we here? Are we there? Is it now? Is it then? They will not know and neither do we (Insert last name of author, page of quote).

Reading this, one feels the brevity of one own’s life and the impermanence of our human creations (or destructions for that matter). Pamela L. Travers must have felt rather small and insignificant, lost in a vastness of something beyond human comprehension. What is the meaning of it all? Pamela L. Travers does not know but the pain of the question remains forever present in her writings.

After the service, the children ask the narrator why there were no wild animals at the crib. “Haven’t they got something to give?” In response, the narrator finds herself, like in a dreamlike state, telling the children the missing verse in the carol; the verse about the Fox. She then proceeds to tell them the story of the “Fox at the Manger,” which can be compared to a sort of fable where the dialogues between the animals convey a moral to the reader. What is the moral? And who does the Fox personify? I will tell you more in next week’s post.