Dear Reader,

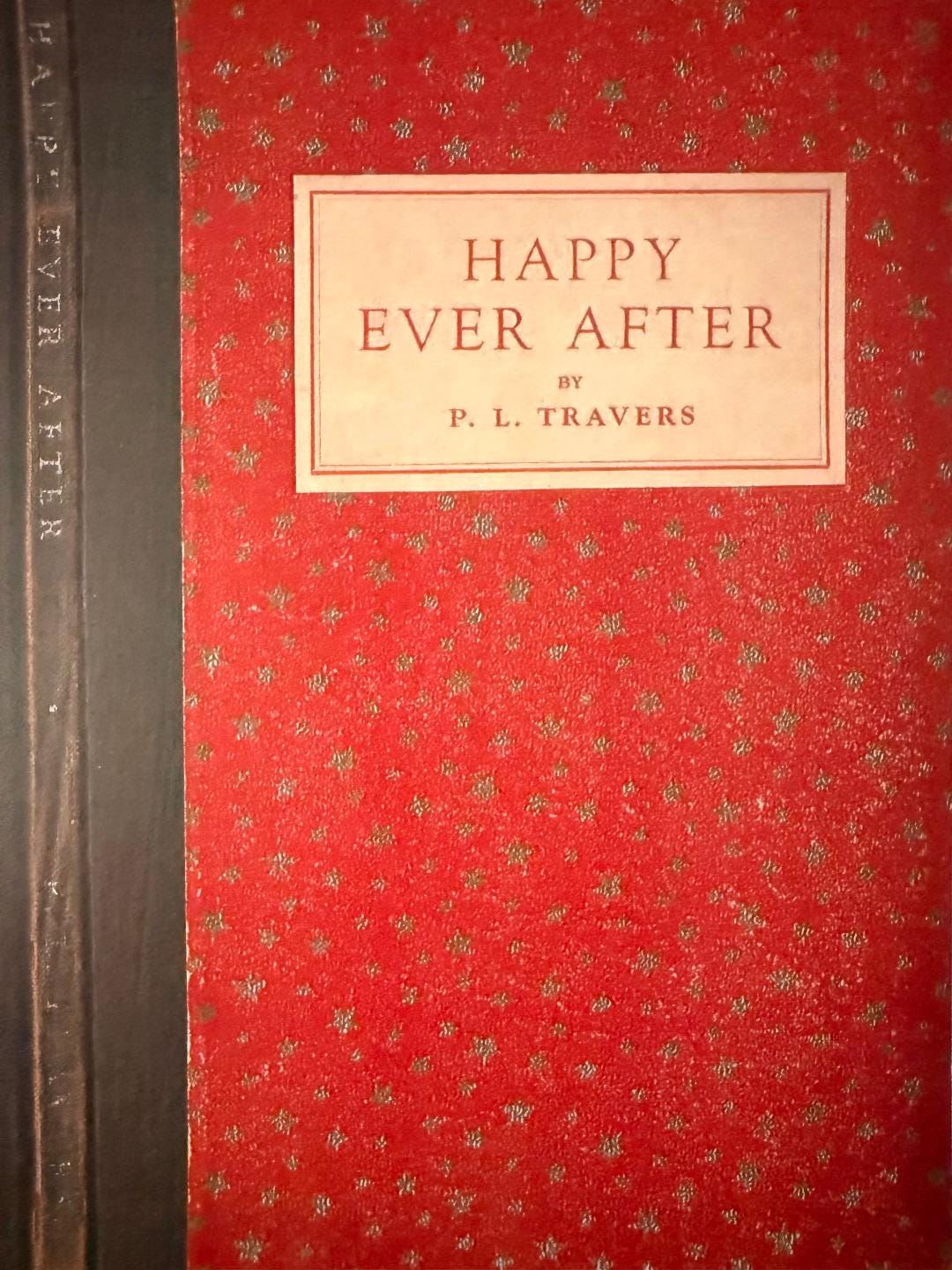

I wish I were as talented a storyteller as P. L. Travers, able to gift you a magical story this holiday season, but my brain is analytical and reflective. So instead of enchantment, what I am offering is a comparative analysis of the first version of “Happy Ever After,” a Mary Poppins story by P. L. Travers first published privately for friends in 1940 and later included in Mary Poppins Opens the Door, the third book in the series, published in 1943.

The first edition of “Happy Ever After” was limited to one thousand copies privately published by the author for her friends and her publishers as a New Year’s greeting. What a lovely idea, and how lucky were those who received it!

When I first sat down to read the original version, I did not know what to expect, though I suspected there would be some differences from the story I had read in Mary Poppins Opens the Door. Naturally, I was curious to see what had changed and perhaps even to investigate the differences and what they might reveal.

It turned out that the original story is very similar, with most of the differences being largely stylistic. That will likely come as no surprise to any writer. Editing, polishing, and improving a text can be a never-ending process, especially when one struggles with perfectionism or insecurity, which may simply be two sides of the same coin. However, I noticed two significant discrepancies between the two versions of the story and these are the ones that I want to tell you about.

Nowhere in the Mary Poppins books is the exact age of the Banks children stated. The reader understands that Jane and Michael are preschoolers, since they spend most of their time with Mary Poppins in the nursery or in the park. John and Barbara grow from babies to toddlers, and the youngest Banks child, Annabel, appears in the second book, Mary Poppins Comes Back (1935).

But in the 1940 edition of “Happy Ever After,” P. L. Travers reveals how she imagines the ages of the children, and interestingly she seems to forget about Annabel. Or perhaps she intended the story to take place between Mary Poppins’s first visit to the Banks family in Mary Poppins (1934) and her second visit in Mary Poppins Comes Back (1935).

“It was the latest day of the Old Year. Upstairs in the nursery of Number Seventeen Cherry Tree Lane, Jane Banks who was seven, Michael Banks who was five and John and Barabra Banks who were twins and two-and-a-half, were being undressed.”

This is certainly the kind of detail only a Mary Poppins enthusiast like me would notice, but I take enormous pleasure in diving deeply into these stories and sharing my findings with you. I hope you enjoy reading about them as much as I enjoy discovering them.

Another interesting difference between the two versions is that in the 1940 edition, P. L. Travers describes at length how the children perceive Mary Poppins. In the later version, which I find more successful, she conveys the same idea more succinctly and in a way that feels more revealing. Here are the two passages in order.

“She moved about the nursery, folding up the scattered clothes and tidying away the toys. To look at her – with her coal-black hair, her china-blue eyes, her bright pink cheeks and her turned-up nose that was like the nose for a Dutch Doll – you would never imagine that she was anything but a perfectly ordinary person. But Jane and Michael and John and Barbara knew better. For had she not, when she first arrived at Number Seventeen, mounted the stairs by sliding up the banisters? And was it not certain that on her second visit she had appeared from Nowhere on the end of a string, looking more like a kite than a human being? How could a perfectly normal ordinary person be capable of such extraordinary behaviour? Impossible. Jane and Michael and John and Barbara knew very well how extraordinary she was but they did not speak of it for there were things about Mary Poppins that could never be explained. And it was no use talking to her about it for Mary Poppins, as everybody knows, never told anybody anything.”

The passage comes across as clunky and overly explained, and P. L. Travers may have added extra detail for friends unfamiliar with Mary Poppins, but she later trimmed it from 182 words to 94 in the second version of the story.

“She moved about the Nursery, folding up the scattered clothes and tidying the toys. The children lay cosily in their beds, watching the crackling wing of her apron as it whisked about the room. Her eyes were blue and her cheeks were pink and her nose turned up with a perky air like the nose of a Dutch Doll. To look at her, they thought to themselves, you would never imagine she was anything but a person. But, as you know and I know, they had every reason to believe that Appearances are Deceptive.”

What a valuable lesson for children and one that resonates deeply, yet is often forgotten as we grow older. The importance of looking beyond outward appearances and not relying solely on what meets the eye is especially relevant in today’s world, where social media shapes so much of our perception. We are constantly exposed to carefully curated images and stories that can distort what is real and influence how we view ourselves and others.

It’s all too easy to fall into the trap of comparing and judging based on these surface impressions. Many of us have likely experienced firsthand how the tendency to compare ourselves with others can disrupt our relationships and undermine genuine connections. Although it is natural to observe and compare, I find that the rise of social media has intensified these impulses, often resulting in feelings of envy, dissatisfaction, and a sense of inadequacy. Ultimately, the gentle reminder from Mary Poppins to look deeper and not be deceived by appearances is a lesson we would all do well to remember, especially in our modern, image-driven world.

I often wonder what would P.L. Travers think of the world we now live in.

Now I would like to share some examples of the stylistic changes made in the story, even though I cannot fully explain the reasons behind these edits:

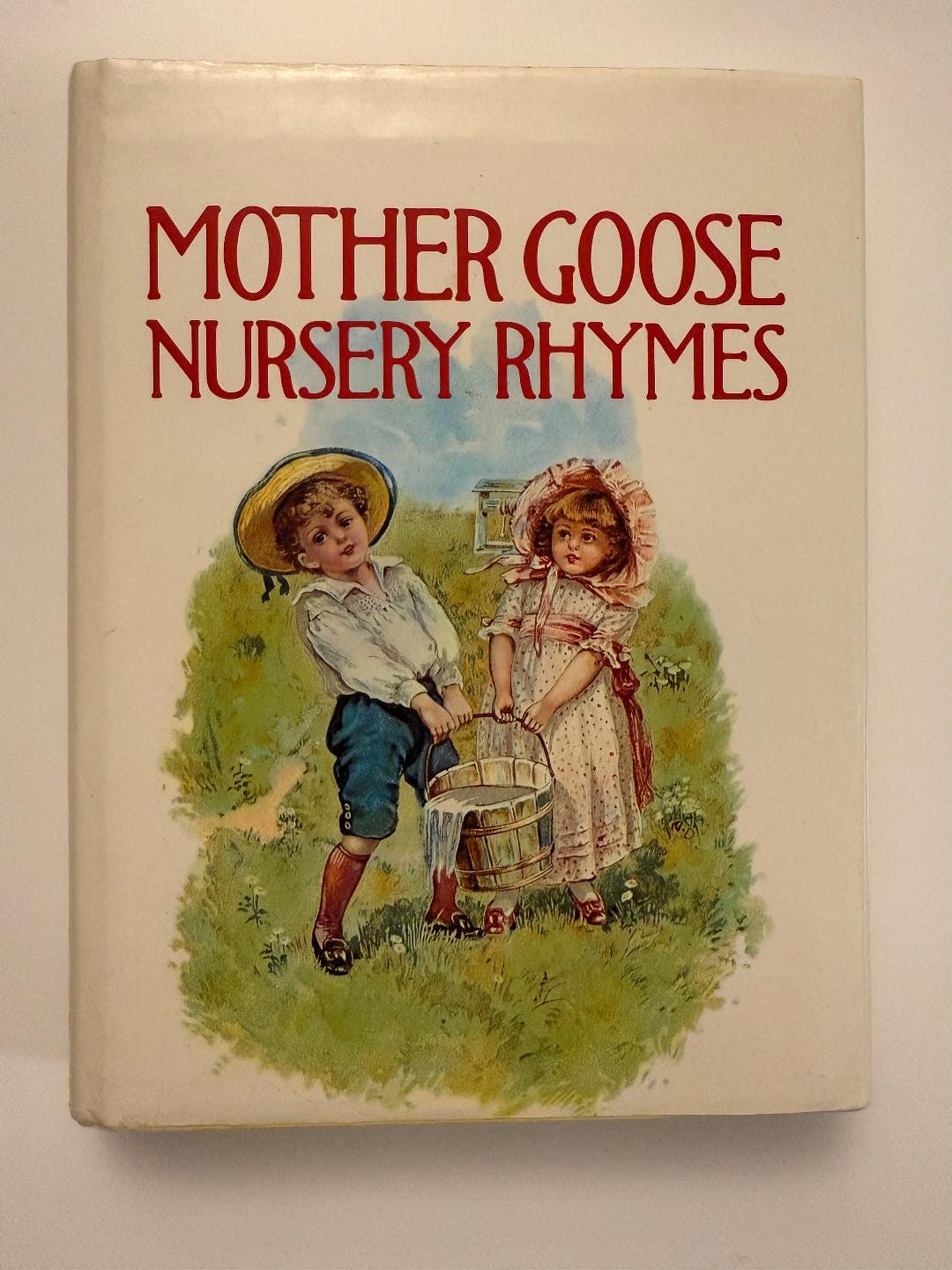

In the 1940 version, the nursery characters that come to life on New Year’s Eve are drawn from Nursery Rhymes Old and New, a Victorian era edition of classic English nursery rhymes. In the 1943 version, however, the characters come from Mother Goose Nursery Rhymes, which refers not to a single book but a long-standing tradition of collections featuring familiar English rhymes and characters.

In the 1940 version Admiral Boom blows a trumpet in the frosty air while in the 1943 story he clangs a ship bell.

In the 1940 version, Barbara’s monkey toy is called Sissie, while in the later version the toy is renamed Pinnie.

In the first version, when the children follow their toys to the park where characters from fairy tales and nursery rhymes have gathered to celebrate a magical moment of happy ever after, the brief crack between the first and last stroke of midnight on New Year’s Eve, they are greeted by the Frog Who Would a-Wooing Go. In the second version, however, they are welcomed instead by the Three Blind Mice and the Farmer’s Wife.

There are several similar small changes in the second version of the story, although the reasons for them are not entirely clear. Even so, the heart of the narrative remains unchanged, reminding us that we each must work to reconcile the opposing forces within our inner and outer lives.

Wishing you all a happy ending of the old year and an even happier start of the new year.

Warmly,

Lina

Discover more from LINA SLAVOVA

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.