Pamela L. Travers stemmed from a religious soil. She heard readings from the Bible and attended church services on Sundays at St. David’s Anglican Church of England in Allora, Queensland, Australia.

Her parents were pious churchgoers; thus, God was an absolute and uncontestable part of Pamela’s reality:

…God ubiquitously worked among us, forever unespied – playing the organ on Sundays, his feet bare on the pedals…..Once He looked me at through the gap in the fence with the face of a golden sunflower, awesome, quizzical, resolute. I put up my hand and I picked Him.

Curious enough, despite her parents’ piety, this almost transcendental experience once shared was dismissed as inappropriate: “No one, they said, could pick God and if they could they would not. It was socially, if not ethically, unacceptable and not the kind of thing people did.”

Yet, it was not these insensitive comments but her father’s sudden death that shook the foundations of Pamela L. Travers’s religious beliefs. She had no choice but to accept her father’s death, even if the process took her several years. What she failed to accept, however, was a God who allowed for such a loss. By losing her father she also lost her religion.

Alas, she did not lose her spiritual needs. A deep inner void remained to be filled. And that explains her lifelong following of the esoteric teachings of George Ivanovich Gurdjieff (whom she met in her late thirties), as well as her general restlessness and search for spiritual masters.

Strangely, despite her rejection of the God from her childhood, Pamela kept a faint connection to her Christian upbringing. Some of her less known writings (“Ah Wong,” “Johnny Delaney,” “I Go By Sea, I Go By Land,” and “Fox at the Manger”) contain religious references which leave a vague impression of an ambiguous belief system. And it is to be noted that Gurdjieff himself called his system esoteric Christianity because of his ideas about sacrifice and voluntary suffering. A similar conclusion can be drawn about her interest in the Durkheim’s system which is a combination of Christian and Zen concepts.

However, the major difference between her earlier religious training and the Gurdjieff’s and Durkheim’s teachings is that in these teachings the divine is described in a more mystical manner. There is also a strong emphasis on physical exercises as a gateway to a higher level of consciousness; ritual dances in the case of Gurdjieff and yoga and breathing exercises with Durkheim. In both systems, the process of personal growth is entirely the individual’s responsibility; an experiential inner process to be discovered by the individual on the spiritual path. Truth is to be experienced not known.

In 1943, Pamela L. Travers (at that time already a follower of Gurdjieff) wrote the story of “Ah Wong” as a Christmas present for her friends. She did not intend the story for the public eye and it was only in November 2014 that it became available for the general reader. Virago Press, with the authorization of Pamela’s estate, published Aunt Sass a compilation of three stories: “Aunt Sass,” “Ah Wong,” and “Johnny Delaney.” The story of “Aunt Sass” was previously discussed on this blog. It features Pamela L. Travers’s great-aunt Ellie (under the name of Aunt Sass) who was, to a certain extent, the inspiration of the character of Mary Poppins.

Also, just as in “Aunt Sass,” a child’s voice tells the story of “Ah Wong” and again, as in “Aunt Sass,” it contains some biographical elements form Pamela’s Australian childhood.

The Travers’s household in the early years, before her father’s death, employed a Chinese cook who left a lifelong impression on Pamela’s heart.

In the story, Ah Wong arrives out of nowhere, as an angel of providence, just at the right time when the family has lost their incompetent Chinese cook to a work-related injury. Ah Wong, thin and wrinkled with a long, black pigtail swinging underneath his hat, is described as a benevolent, energetic, and caring force:

For Ah Wong did not merely cook for the family. It soon became apparent that he owned the family. He darted like lightning about the house, dusting, making beds, sweeping and polishing.

Pamela L.Travers presents Ah Wang as the ultimate house elf: “Flowers bloomed, green rows of vegetables appeared, watermelons swelled like balloons. It was our belief that Ah Wong blew them up at night.”

Now, this sweet man remained profoundly engraved in Pamela’s memory not only because of his loving care for the family, but also and probably more so, because he was different in a time and place of Christian homogeneity. Something mysterious was hidden behind a beaded curtain in his room; Ah Wong was bowing to a “heathen idol.”

Thus, Pamela and her siblings found themselves on a quest:

We were going to convert Ah Wang. At this period, we were immersed in those old stories wherein small children of extreme physical debility set so saintly an example that grown-up sinners were thereby brought to repentance.

The rest of the story goes on in a humorous way to describe the children’s efforts to teach Ah Wong the basics of Christianity and get him christened, of course, all without any success. It is in this story of Ay Wong that we glean Pamela L. Travers’s early religious education:

First, she mentions The Book of Common Prayers which I learned is a compilation of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion, as well as by the Continuing Anglican, the “Anglican realignment,” and other Anglican churches. The book also includes the complete forms of service for daily and Sunday worship.

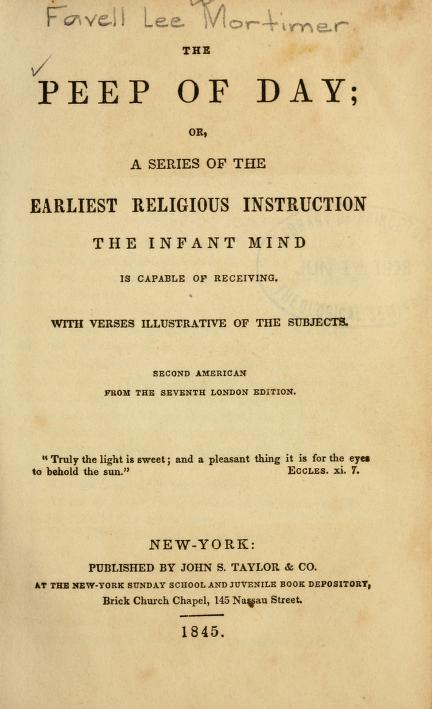

Then, she tells us that her Bible primer was the Peep of Day and that Ah Wong succeeded in learning the prayers. So, I looked it up, and Peep of Day turns out to be a series of religious instructions for young children with illustrative verses written by Favell Lee Mortimer.

The book is separated in sections as follows:

Section 1: My Family and Me – Body, Parents, Soul

Section 2: Angels – Good Angels, Wicked Angels

Section 3: God’s World – The World (3 lessons), Adam & Eve, The first sin, The Son of God

Section 4: Jesus has Arrived – Virgin Mary, Birth of Jesus, Shepherds, Wise Men, King Herod

Section 5: Jesus at Work – The Temptation, 12 disciples, First miracle, Several miracles, Sinner & Simon, Storm at Sea, Jairus’ daughter, Loaves and fishes, Kindness of Jesus, Lord’s prayer, Jesus foretells his death, Lazarus, Jesus in Jerusalem, The Temple, Judas

Section 6: The Last Meal – The Last Supper (3 lessons)

Section 7: The Final Night – The Garden, Peter’s denial, Pontius Pilate, Death of Judas

Section 8: Jesus Dies – The Cross (3 lessons), The Soldiers, The Grave

And here is a verse from the Peep of Day which we can imagine Ah Wong and the Children sang together:

My little body’s made by God

Of soft warm flesh and crimson blood;

The slender bones are placed within,

And over all is laid the skin

My little body’s very weak;

A fall or blow my bones might break;

The water soon might stop my breath;

The fire might close my eyes in death.

But God can keep me by his care.

Ah Wong indulged the children by playing and listening to their stories, but when they described to him the glorious picture of their father at the Church service, trying to convince him to come with them, Ah Wong found the idea of giving money at the end of the service completely ludicrous.

….our father, in his white silk suit with the crimson cummerbund, taking round the plate. This, to us, was a sight ever glorious. Sunday after Sunday we thrilled with pride as, singing the last hymn in a roaring baritone, Father took up the collection.

“Whassa dam-silly-fellow nonsins? he shouted wrathfull. ‘Boss take-im money? I don’t tink so. Boss not take-im Ah Wong’s money.”

After this incident, we learn that Ah Wong is saving his money to return to China. Soon after that, the tone of the story abruptly changes and becomes darker. The father suddenly dies and the family must leave its sugar plantation and its Chinese cook. Many years later, the child narrator, now a young journalist, meets Ah Wong on board of a ship sailing to China. Ah Wong is part of the ship’s cargo, a dying stock of old Chinese men on the way to their homeland. The story ends on a somewhat lyrical reflection about life and death being one river: “The same flood that was flinging me into life was taking Ah Wong home…”

I’m bookmarking your site. Not only is Pamela L. Travers extremely interesting, but your analysis is extremely insightful and well written. ❤

LikeLike

Thank you so much!!! I am putting all I have in this project. I post once per week. Glad to have found your blog as well 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much!!! I am putting all I have in this project. I post once per week. Glad to have found your blog as well 🙂

LikeLike

I really love the religious idealogies explored in this piece. It is relatable, regardless of one’s religious background. I grew up Christian, with a grandfather as a Methodist preacher and certainly had some trying life experiences, challenging my belief system. I studied shamans and mysticism in college, so I was glad you touched on the physical element of spiritual enlightenment. The themes all ring so true — especially the notion that the death of one’s religion leaves one with a vast spiritual void, still desperately seeking fulfillment. It’s so interesting — both stunningly beautiful and depressingly dark — to examine various people and their unique stories to see how we all adapt to pre-existing religious dogmas based on our unique perspective shaped by our own experiences… then have to cope with fallacies, false promises, or conflicting narratives. I fully agree that “truth is to be experienced, not known.” Reminds me of a quote from a lawyer I recently read: “Chase after the truth like all hell and you’ll free yourself, even-though you never touch its coat-tails.” -Clarence Darrow. Any-who, glad to have stumbled upon your blog!

LikeLiked by 1 person

With regards to her losing her Christian faith as a young girl, do you have any thoughts about her concluding Mary Poppins Opens the Door (which, as far as she knew at the time, was Mary Poppins leaving her own life for good) with “Gloria in Excelsis Deo“?

LikeLike

I am not saying she denigrated her Christian upbringing, only that it was no longer enough to explain the mysteries of life. She studied other religions and she focused on the mystical branches of these religions. I would be interested in reading your thoughts on the use of “Gloria in Excelsis Deo “

LikeLike

Please excuse the nearly two year delay!

Pamela certainly believed in a creator (“Do stop talking about creating. C.S. Lewis said another very wise thing; he said there is only one creator and we merely mix the elements of existence. I like that. I don’t like people swaggering around and calling themselves creators.”), even if it wasn’t necessarily the Abrahamic God. I think that perhaps she didn’t use the phrase in the sense it’s traditionally used in, as a hymn to the Abrahamic God, but rather as simply to say “Glory to the highest creator” that Mary Poppins and herself came out of, and the name for that creator in Latin is Deus. As for why she chose to say it in Latin, which is often used in ceremonial and spiritual contexts, perhaps it was to (as far as she knew) end the series with a sort of reverence for the otherworldly mysteries of Mary Poppins.

LikeLike